The History of CF services in Leeds

The Origins and Development of the Leeds Regional Cystic Fibrosis Unit (Pt. 1 & Pt 2)

The events preceding and influencing a particular occurrence or development are many and complex. Some are clear but many are subtle and not immediately obvious. In this context I often wonder how it was that the first officially recognised and funded Regional Paediatric CF Service in the UK developed during the Eighties in a northern city, Leeds, in the city’s old infectious disease hospital, Seacroft, where there were many of the city’s general paediatric beds. Furthermore, a general consultant paediatrician who had failed to obtain the NHS consultant appointment in the city’s main teaching hospital, had started the CF clinic.

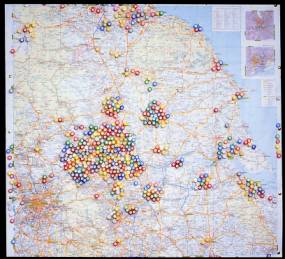

In the pages that follow I will try to answer some of these questions. For example how, in the late Seventies, this small monthly paediatric outpatient clinic for babies with CF represented the start of one of the UK’s major CF centres with a national and international reputation. By 2015 the number of children and adults with CF attending the paediatric and adult Leeds CF centres (228 children & 437 adults – total 665) was exceeded only by the number attending those at the Royal Brompton in London (335 & 671 – total 1006) and marginally by those attending the Manchester clinics (323 & 426 – total 749).

The first paediatric clinic sessions devoted entirely to CF in Leeds, indeed in Yorkshire, started as a monthly Monday afternoon session in my outpatients at Seacroft Hospital, Leeds in 1977/78. I will describe in some detail how this came about in the pages that follow.

Progress has not always been easy or approved of by some of my paediatric consultant colleagues. However Dr. Henry Heimlich’s advice to Dr. Robert Wood, after the latter’s first major presentation on flexible bronchoscopy in infants and young children had received a mixed reception, seems relevant – “Bob” he said “if at any time in your career you find your peers are all comfortable with what you are doing you may as well hang it up. You’re no longer being creative”. Woods found this to be good advice. It is certainly true that anything new or different in medicine usually receives initial opposition from some colleagues. I certainly found this to be so in Leeds!

Situation regarding CF in the UK prior to the late Seventies

During the Sixties and Seventies the situation in Leeds and the Yorkshire region regarding cystic fibrosis (CF) was similar to that in most other regions of the United Kingdom. There were no specialist CF centres as we know them today although a few paediatricians such as Winifred Young and Margaret Mearns at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Hackney and Archie Norman at Great Ormond Street in London had developed a special interest in cystic fibrosis. In contrast, in the USA Leroy Matthews and Carl Doershuk in Cleveland had developed and published details of their “comprehensive and prophylactic (preventive) and therapeutic treatment program” for treatment of cystic fibrosis. Their programme developed and eventually became the model for the CF Foundation’s CF centre programme from the early Sixties. (Doershuk et al, 1964 & 1965 below).

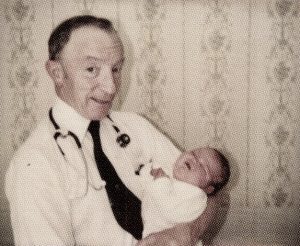

- Leroy Matthews

- , Carl Doershuk

- Archie Norman

- Winifre Young

- Margaret Mearns

- Sir John Batten

–Matthews LW, Doershuk CF, Wise M, Eddy G, Nudelman H, Spector S. A therapeutic regimen for patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 1964; 65:558-575. [PubMed]

– Doershuk CF, Matthews LW, Tucker A, Spector S. Evaluation of a prophylactic and therapeutic program for patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 1965; 36:675-688. [PubMed]

Prior to the Eighties there were few children with CF in the UK as most died in infancy or early childhood hence there were virtually no adults except at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London; Sir John Batten one of the physicians there started the clinic for CF adults there in the mid-Sixties to carry on the care of the surviving children who had

been treated at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children Hackney, Great Ormond Street or by Dr. David Lawson at Carshalton. Most children with CF elsewhere in the UK attended their local hospital and were under the care of the local consultant general paediatrician who treated them until they died.

Sir Robert Johnson

Sir Robert Johnson, a parent of two CF children and founder member ofthe UK CF Trust, in a lecture at the 1984 Brighton CF Conference, described the situation in the UK in the early Sixties – “the general picture here was of ignorance and distress unmitigated by hope or practical effective action”.

The full, illustrated text of Sir Robert’s very interesting lecture describing the early history of the CF Research Trust is in this “More History” section of this website.

Cystic fibrosis in Yorkshire in the Sixties

An article in 1967 on the incidence and life expectancy of children with CF describes a survey from Yorkshire written by two local consultants Drs. Richard Pugh of Hull and Dr Douglas Pickup of Pontefract on behalf of the members of the Leeds Regional Paediatric Club (Pugh & Pickup, 1967).

One hundred and thirty-two infants were confirmed as having CF from a total of 546,764 births over thirteen years – an incidence of 1/4142. Fifty-six infants (42%) died in the first year and most died in early childhood. These figures would be typical of the situation in the UK at the time where virtually all children, with exception of those with serious congenital heart disease, would be treated at their local hospital; there would usually be one or two paediatricians in each town or city. The situation in the Leeds region was representative of the rest of the UK apart from perhaps Great Ormond Street and Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hackney.

– 1967 Pugh RJ, Pickup JD. Cystic fibrosis in the Leeds region: incidence and life expectancy. Arch Dis Child 1967; 42:544-545.[PubMed]

The first major advance towards understanding the cause of CF

The significant increase in salt content of the sweat of people with CF was described in 1953 by Paul di Sant’Agnese in New York (di Sant’Agnese et al, 1953); he succeeded in explaining why 7 of the 10 children admitted with heat prostration in a major heat wave in New York in 1948 had cystic fibrosis (Kessler & Andersen, 1951). Undoubtedly the first major advance during the Fifties was this recognition of the increased salt content in the sweat of people with CF. Subsequently over the next ten years the availability of the sweat test permitted an accurate diagnosis when CF was suspected and gradually replaced the more invasive duodenal intubation to obtain duodenal juice to determine the tryptic activity – which was low or absent in cystic fibrosis.

- Paul Di Sant’Agnese

- From the original paper

- Robert Darling

This 1953 publication is the main paper that di Sant’Agnes himself quotes as deescribing the sweat electrolyte abnormality expanding on their initial paper (Darling et al, 1953). Di Sant’Agnese mentions the original report of Kessler and Andersen 1951.

Paul Quinton ResearchGate

Paul Quinton (who later described the impermeability of the sweat glands) recalled that di Sant’Agnese told him that the development of heat tolerance among troops sent to North Africa was attributed to adaptations to sweating; so di Sant’Agnese decided to pursue excessive salt loss in the sweat as the most likely origin of volume depletion during the high heat stress (Quinton, 1999).

Robert (Bob) Darling was head of Rehabilitation at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital and had a constant temperature room. Di Sant’Agnese decided “as a shot in the dark to see if sweating function was impaired in CF patients that would lead to a smaller than normal volume of sweat, or whether there was something wrong with the sweat electrolyte concentration”. He continued – “In April 1952 two teenage children with CF and two controls were put in the constant temperature room and their sweat then analysed for electrolytes. To my surprise and excitement the answer was right there. There was a tremendous difference in the sweat electrolyte concentration between the two groups”.(figure). “In contrast the sweating rate was similar in the two groups”.(Described in detail by Paul di Sant’Agnese. Experiences of a Pioneer Researcher. In: Doershuk CF (ed.) Cystic Fibrosis in the 20th Century 2001; Fanos JH. 2008; 17-35.).

– Kessler WR, Andersen DH. Heat prostration in fibrocystic disease of the pancreas and other conditions. Pediatrics 1951; 8:648. [PubMed]– Darling RG, di Sant’Agnese PA, Perera GA, Andersen DH. Electrolyte abnormalities of the sweat in fibrocystic disease of the pancreas. Am J M Sc 1953;225:67-70 [PubMed].

– di Sant’ Agnese PA, Darling RC, Perera GA, Shea E. Abnormal electrolyte composition of the sweat in cystic fibrosis: Clinical significance and relationship to the disease. Pediatrics 1953; 12: 549-563. [PubMed]

– Quinton PM. Physiological basis of cystic fibrosis: a historical perspective. Physiol Rev 1999; 79:S3-S22

di Sant’ Agnese PA, Darling RC, Perera GA, Shea E. Abnormal electrolyte composition of the sweat in cystic fibrosis: Clinical significance and relationship to the disease. Pediatrics 1953; 12: 549-563. [PubMed] In this classic study the authors examined 43 people with CF, nine patients with other pancreatic diseases and 50 controls in a room at 32.2 C for one to two hours. Sweat was collected onto dry gauze under adhesive waterproof plaster. Sweat chloride in the CF patients was 106 (60-160) meq/l, in controls and other pancreatic diseases only 32 meq/l (4-80) and in CF the sodium was 133 (80-190), and in controls 59 meq/l (10-120).

This was undoubtedly the most important advance in the understanding of CF up to that time when no one had any idea as to the cause of the condition. However, astonishingly, di Sant’Agnese recalls their paper received a very cool reception at the 1953 meeting of the American Pediatric Society with not a single question!!

Shwachman

Also when it was presented before Jas Kuno, apparently a distinguished sweat physiologist, Kuno uttered one word -“impossible”- and walked out of the room! It is also said that even di Sant’ Agnese’s close New York colleague Dorothy Andersen was at first reluctant to accept the findings. However, and perhaps predictably, the legendary Harry Shwachman of Boston, for many years one of the leaders in CF research and care, soon visited di Sant’Agnese in New York; he was impressed and with his usual alacrity and energy by October 1954 was able to present a large supportive series of sweat test results in children with CF much to di Sant’Agnese’s delight.

There were early problems with the sweat test

During the late Fifties the raised salt content of the sweat became the main diagnostic test. However, there were some early problems in collecting suitable quantities of sweat of small children. I remember, as a student locum house physician in the mid Fifties, unsuccessfully trying to collect sweat from children by enclosing a limb in a Bunyan bag – a plastic bag used for treating burned limbs!

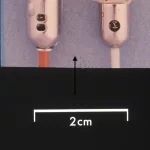

During the Fifties, prior to the description of the pilocarpine iontophoresis method of stimulating sweating (Gibson & Cooke, 1959), already debilitated infants were heated in plastic bags and blankets to induce sweating, at times with serious side effects (Misch & Holden, 1958). The patient was “placed in a plastic bag tied loosely around the neck (figure) and allowed to lie in a cot or bed covered with three or four blankets. The sweat was collected on weighed filter papers that were applied to the back (figure). In some instances the children were restive at first but quickly became used to the conditions” (Webb et al, 1958).

– Webb BW, Flute PT, Smith MJH. The electrolyte content of the sweat in fibrocystic disease of the pancreas. Arch Dis Child 1957; 32:82-84.

– Misch KA, Holden HM. Sweat test for diagnosis of fibrocystic disease of the pancreas. Arch Dis Child 1958; 33:179-180.[PubMed]

In 1964 after a six month spell at the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street in London (GOS) I returned to Leeds as a lecturer in paediatrics with Professor Stuart Craig’s University Department. In London I had observed Tom McKendrick, then a senior registrar there performing a series of sweat tests using the recently described pilocarpine iontophoresis method of stimulating sweating (Gibson & Cooke, 1959).

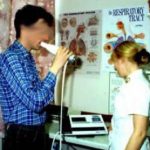

pilocarpine electrophoresis

sweat collection

I was impressed by the iontophoresis method and so, when I returned to Leeds in 1964 I obtained the Professor’s permission to purchase Gibson and Cooke pilocarpine iontophoresis equipment. Mr. Alan Steel, our excellent Seacroft biochemist, had been performing sweat tests from the mid-Fifties using whole body heating of children admitted to the ward. He readily agreed to change to this new method of stimulating sweating. In the figure Dr Leonie Shapiro (who later performed our sweat tests at St James’s for many years after 1980) is using the pilocarpine iontophoresis method to collect a sweat sample.

– 1959 Gibson LE, Cooke RE. A test for concentration of electrolytes in sweat in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas utilising pilocarpine electrophoresis. Pediatrics 1959; 23:545-549.

– McKendrick T. Sweat sodum levels in normal subjects, in fibrocystic patients and their relatives and in chronic bronchitis patients. Lancet 1962;1;183-186.

1964 A reliable sweat testing service developed at Seacroft and subsequently at St James’s University Hospital, Leeds

So from the early Sixties a reliable sweat testing service was provided at Seacroft Hospital by our biochemist Alan Steel. This was a major advance in improving the safety and reliability of CF diagnosis. Soon paediatricians from surrounding towns were referring children to Alan Steel at the Seacroft Laboratory for sweat tests. Even by the late Sixties reliable sweat tests were available in only a few hospitals in Yorkshire and the results could be unreliable in inexperienced hands leading to over-diagnosis. Over-diagnosis was first reported from Professor Charlotte Anderson’s unit in Birmingham (Smalley et al, 1978). In fact, for occasional operators, the sweat test was fraught with potential mistakes, with potentially disastrous results as we subsequently described. On reassessment of the first 179 children who had previously been diagnosed as having CF and referred to our unit in Leeds for comprehensive assessment of their CF, we found no less than 7 (4%) did not to have the disorder. Although the parents were relieved, many were angry at the years of unnecessary treatment. Also some had decided to avoid the 1:4 risk of having further children (Shaw & Littlewood, 1987).

– Smalley CA, Addy DP, Anderson CM. Does that child really have cystic fibrosis? Lancet 1978; ii: 415-417.

– Shaw NJ, Littlewood JM. Misdiagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1987 Dec;62(12):1271-3.

Occasional children were referred to me as possibly having CF

On occasion, a paediatrician, who had referred a child to Alan Steele for a sweat test, would ask me, by then an experienced paediatrician, to see the a child for an opinion. In the Seventies we were not encouraged to take over the care of children referred for a second opinion; the concept of sub-specialisation was still in its infancy at the Seventies. The situation remained unchanged re-CF even after the mid-70s. Even in the Eighties one professor of paediatrics was heard to remark, “Any paediatrician worth his salt should be able to look after a cystic!”

The decade following my appointment as an NHS consultant paediatrician in 1968 – a time for extensive general experience during the Seventies

Following my appointment as an NHS consultant in 1968 in Leeds, I became a hard working, but happy, general paediatric consultant with an increasingly busy consulting practice in Leeds and the surrounding area. I was prepared to see any child with a problem, anywhere, any time, privately or as an NHS patient; respiratory or gastrointestinal problems were frequent referrals. The many children referred presented many interesting and difficult clinical problems. I had a fruitful collaboration with our staff and many colleagues at Seacroft and St James’s University Hospital.

This experience during the Sixties and Seventies formed the basis of a number of varied publications and provided a broad experience of paediatric medicine, which proved very valuable when dealing with CF children e.g. newborn screening, respiratory problems, nutritional and gastroenterological disorders, and later even diabetes.

Through the Seventies I also still had a major commitment to neonatal care and was responsible for the supervision of 3000 newborns at St Mary’s Maternity Hospital in Bramley, Leeds. I also ran a large asthma clinic, a gastroenterology clinic, provided a jejunal biopsy service, a urinary infection clinic and even a paediatric diabetic clinic – in fact, I became an experienced and and very general paediatrician – or perhaps others would describe me as a “jack of all trades”! Obviously it would be impossible today. However, I always favoured the idea of specialised clinics where one could collaborate with expert colleagues such as other clinicians, laboratory workers, physiotherapists, dietitians, experienced nurses and could work as part of a team – a technique which eventually formed the basis of the Regional CF Service.

From an early stage I always enlisted the help and expertise of colleagues be they medical, surgical, nursing, allied professionals, laboratory workers – this was undoubtedly an important characteristic when building up our CF team. Following President Woodrow Wilson’s philosophy – “I not only use all the brains that I have, but all that I can borrow”. Also I encouraged those colleagues with whom we cooperated to become involved in research relating to the clinical problems that we were encountering that were relevant to their own expertise and speciality.

The publications from colleagues and myself during this “pre-CF” phase up to 1980 reflect this tendency. The publications include one or more chemical pathologists, biochemists, laboratory technicians, neurologists, radiologists, nurses, adult physicians, general practitioner in addition to my immediate junior paediatric staff and colleagues.

– Littlewood JM. Candida infection of the urinary tract. Case report, with a review of the literature and a study of frequency of yeast isolations from the urine of children with bacterial urinary infections. Br J Urol. 1968 Jun;40(3):293-305.

– Dickinson JP, Holton JB, Lewis GM, Littlewood JM, Steel AE. Maple syrup urine disease. Four years’ experience with dietary treatment of a case. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1969 Jul;58(4):341-51.

– Littlewood JM. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. Br Med J. 1969 Aug 16;3(5667):416. PMID: 5797794

– Littlewood JM, Kite P, Kite BA. Incidence of neonatal urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 1969 Oct; 44(237):617-20. PMID: 4981204

– Littlewood JM. Spina bifida. Nurs Times 1970; 66(1):5-8

– Littlewood JM, Hunter I, Payne RB, Miles DW. Placental transfer of an IgG paraprotein associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Br Med J. 1970 Oct 10;4(5727):94-5. PMID: 5471777

– Littlewood JM. White cells and bacteria in voided urine of healthy newborns.Arch Dis Child. 1971 Apr;46(246):167-72. PMID: 5576025

– Littlewood JM. 66 infants with urinary tract infection in first month of life.Arch Dis Child. 1972 Apr;47(252):218-26. PMID: 5023470

– Littlewood JM. Letter: The prevalence of bacteriuria in full-term and premature newborn infants. J Pediatr. 1973 Nov; 83(5):888-9. pMID: 4742588

– Davies JM, Gibson GL, Littlewood JM, Meadow SR. Prevalence of bacteriuria in infants and preschool children. Lancet. 1974 Jul 6;2(7871):7-10. PMID: 4134405

– Kissach AW, Currie S, Harriman DG, Littlewood JM, Payne RB, Walker BE. Letter: Leigh’s disease and failure of automatic respiration. Lancet. 1974 Sep 14;2(7881):662. PMID: 4137785

– Arrowsmith WA, Payne RB, Littlewood JM. Comparison of treatments for congenital non-obstructive non-haemolytic hyperbilirubinaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Mar;50(3):197-201. PMID: 1147651

– Meadow SR, Davies JM, Gibson GL, Littlewood JM. Letter: Urinary tract infection in children of preschool age. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Jul; 50 (7):578. No abstract available. PMID: 1167077

– Eastham DG, Littlewood JM, Burton D. Letter: Monoparesis following CPAP. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Aug; 50(8):668-9. No abstract available. PMID: 1106335

– Ghosh SK, Littlewood JM. The clinical picture of coexisting toxoplasma and toxocara infection and its management. A small child with a rare double infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1976 Jan;15(1):31-3. No abstract available. PMID: 1245080

– Littlewood JM, Lee MR, Meadow SR. Treatment of childhood Bartter’s syndrome with indomethacin. Lancet. 1976 Oct 9;2(7989):795. No abstract available. PMID: 61458

– Littlewood JM, Payne RB. Placental transfer of IgG paraprotein with prolonged immunosuppression. Br Med J. 1977 Jan 29; 1(6056): 291. No abstract available.PMID: 837084

– Littlewood JM. Neonatal screening: the present position. Midwives Chron. 1977 May;90(1072):91-3. No abstract available. PMID: 586487

– Ghosh SK, Littlewood JM, Goddard D, Steel AE. Stool microscopy in screening for steatorrhoea. J Clin Pathol 1977 Aug;30(8):749-53. PMID: 599187

– Littlewood JM, Jacobs SI, Ramsden CH. Comparison between microscopical examination of unstained deposits of urine and quantitative culture. Arch Dis Child. 1977 Nov; 52 (11):894-6. PMID: 339849

– Littlewood JM, Lee MR, Meadow SR. Treatment of Bartter’s syndrome in early childhood with prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors. Arch Dis Child. 1978 Jan; 53(1):43-8. PMID: 415668

– Smith SE, Littlewood JM. The two-film barium meal in the exclusion of coeliac disease. Clin Radiol. 1977 Nov;28(6):629-34. PMID: 589918

– Littlewood JM. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Practitioner. 1980 Mar; 224(1341): 305-7. PMID: 7403012

This last was the first paper I wrote on CF at the invitation of Dr. Archie Norman of The Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London who, at the time, was Chairman of the Cystic Fibrosis Trust’s Research and Medical Advisory Committee.

During the Seventies consultants in the Yorkshire Region (“Regional Paediatricians”) increasingly used Mr Alan Steel’s reliable sweat tests and my jejunal biopsy (vide infra) service at Seacroft

The sweat tests performed by Alan Steele from the early Sixties became a well-established service and most paediatricians from Leeds and surrounding general hospitals used the service for their patients.

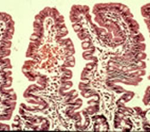

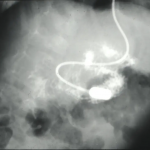

In 1968 I obtained a paediatric sized Crosby intestinal biopsy capsule and started a paediatric jejunal biopsy service; this facility soon attracted referrals from paediatricians in the region to confirm or exclude coeliac disease in their children. We eventually changed to the twin port Kilby modification of the Crosby capsule to use one specimen for histology and the other for disaccharide estimation (Kilby, 1976). In this venture I had the invaluable help of my friend and colleague Dr. Sidney Smith, our paediatric radiologist, for rapid X-ray screening of the capsule into the duodenum, and Dr. Mike Mason the pathologist for histology reports. Later Dr. Avril Crollick was appointed as my Clinical Assistant and eventually performed many of the biopsies until I started using the paediatric endoscope for the purpose. The ability to obtain jejunal mucosa for histological and biochemical examination from children was a relatively recent but major advance in the Seventies.

- Avril Crollick

- Paediatrc jejunal biopsy capsules

- Normal intestinal mucosa

- subtotal villous atrophy coeliac mucosa

- biopsy capsule in small bowel

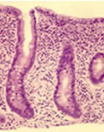

The characteristic histological small bowel appearance of subtotal villous atrophy (SVA – figure) of gluten induced coeliac disease was first identified in 1954 by Paulley, a physician in Ipswich, in laparotomy specimens from four adults with idiopathic steatorrhoea (coeliac disease). In 1957 Margot Shiner was the first to obtain specimens by per oral small bowel biopsy from an 8-year old child; soon a series in children was reported by Charlotte Anderson. In contrast to the subtotal villous atrophy in coeliac disease, in people with CF the intestinal villi are of normal height – in some children with CF they appeared to be even taller than normal.

– Paulley J W. Observations on the aetiology of idiopathic steatorrhoea. Jejunal and lymph node biopsies. BMJ 1954; 173:1318-1321. [PubMed]

– Sakula J, Shiner M. Coeliac disease with atrophy of the small intestine mucosa. Lancet 1957; ii: 876-877. [PubMed]

– Anderson CM. Histological changes in the duodenal mucosa in coeliac disease. Reversibility during treatment with a wheat gluten free diet. Arch Dis Child 1960; 35:419-427. [PubMed]

– Kilby A. Pediatric small intestinal biopsy capsule with two ports. Gut 1976; 17:158-159.

Jejunal biopsy with a paediatric sized Crosby capsule was a relatively new technique in the Sixties. Initially Sir Wilfred Sheldon (a senior consultant paediatrician at GOS) and a senior registrar at GOS, Dr. Eddie Tempany (figure), who was subsequently Professor of Paedaitrics in Dublin.

Eddie Tempany

Eddie and Sir Wilfred considered the investigation to be “outside the scope of routine investigations in children” due to the increased difficulty and risk reported in small children. It is true there were a number of reports of intestinal perforation. However, my delay in starting jejunal biopsies in Leeds was mainly related to the fact that Sir Wilfred Sheldon and our Professor Stuart Craig were old friends and, as I was then a lecturer in Prof Craig’s department, he did not approve of my performing jejunal biopsies. So I had to wait until 1968 when I became an NHS consultant!

Over the next 25 years in my unit we had no serious complications from jejunal biopsies in children aged down to 3 months. Subsequently I have described in detail our experience with over 1000 jejunal biopsies and 108 children with coeliac disease in my friend Professor Peter Howdle’s book (Howdle PD, 1997). Peter eventually succeeded Monty Losowsky as Professor of Medicine at St James’s. He was an excellent and helpful colleague in many areas of gastroenterology where his expertise benefited many of our young patients including those with cystic fibrosis.

Peter Howdle (figure) was a brilliant colonoscopist and his skill in this area was central to the development of our paediatric colonoscopy service – one of the first in the UK (Howdle et al, 1984). Peter taught me how to perform fibreoptic sigmoidoscopies but I never mastered full colonoscopies. His experience with colonoscopies in children was valuable when fibrosing colonopathy was described in the Nineties as a new and worrying complication in some children with cystic fibrosis

Incidentally, from our experience with performing jejunal biopsies for many paediatric colleagues around the Yorkshire region, over 10 years we observed that coeliac disease was becoming less common in young children presumably due to changes in diet (Littlewood et al, 1980).

Professor John Walker-Smith (figure) believes that the development of the technique to perform oral small intestinal biopsy in childhood was the real beginning of paediatric gastroenterology and I would support this view (Walker-Smith, 1997). Certainly to provide a specialist CF service the jejunal biopsy was an essential investigation at the time although immunological tests have become more reliable I recent years.

– Sheldon W, Tempany E. Small intestine per oral biopsy in coeliac children. Gut 1966; 7:481-489.

– Howdle PD, Littlewood JM, Firth J, Losowsky MS. Routine colonoscopy service. Arch Dis Child 1984; 59:790-3

– Walker-Smith JA. Historic notes in pediatric gastroenterology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997; 25: 316

– Littlewood JM. Coeliac disease in childhood. In: Howdle PD (Ed.). Clinical Gastroenterology. International Practice and Research. Bailliere l, London. 1995; 9: 295-328.

– Littlewood JM, Crollick AJ, Richards IDG. Childhood coeliac disease is disappearing. Lancet 1980; ii: 1359.

Paediatric sub-specialities usually followed advances in adults

In the Sixties and Seventies paediatric sub-specialities often developed following the introduction of a specialised investigation that paediatricians learned from adult physicians and surgeons; most were introduced during the Fifties and Sixties The first was obviously cardiac catheterization by paediatric cardiologists in the late Fifties and then came various needle biopsy procedures. These included renal biopsy, percutaneous liver biopsy using the fine Menghini needle and small bowel biopsy during the Sixties.

During the second half of the Seventies a paediatric fibreoptic bronchoscopy was developed by Dr. Robert Wood of Cincinnati (figure) when a prototype paediatric instrument became available leading to the first paediatric flexible bronchoscope in 1978. In 1980 Wood writes “We have utilized a prototype pediatric flexible bronchoscope to perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures on pediatric patients ranging from 840 gm to 14 years of age. Flexible bronchoscopy, with appropriate instrumentation and careful attention to physiological requirements of the patient, is safe and effective in pediatric patients. The availability of new instrumentation promises to have as great an impact on pediatric pulmonology as the standard flexible bronchoscopes did on adult pulmonology. With this instrument, the indications for bronchoscopy may be considerably expanded”

The indications and availability of paediatric flexible bronchoscopy continued to expand and it has even been suggested that every infant with CF identified by newborn screening should be bronchoscoped to obtain cultures from the lower airways (Hilliard TN et al. Arch Dis Child 2007; 92:898-899. [PubMed]). However, provisional data from a more recent major study from Australia by Claire Wainwright would not support this suggestion, as the information from regular bronchial lavages resulted in no better outcome than from routine therapy (Wainwright CE et al 2011).

– Wood RE, Sherman JM. Pediatric flexible bronchoscopy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1980; 89(5Pt1):414-416

– Wood RE. “Pediatric flexible bronchoscopy: The inside story”. In: Doershuk CF, (Ed.). Cystic Fibrosis in the Twentieth Century. Cleveland: AM Publishing Ltd, 2001:112-119.).

– Wainwright CE et al. Effect of bronchoalveolar lavage-directed therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and structural lung injury in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2011; 306:163-171).

Many of these developments occurred in a limited number of centres during the late Seventies and Eighties in the UK so a reliable sweat test and a jejunal biopsy proved to be a powerful, and as yet not widely available, combination for investigating children with significant malabsorption problems and possible cystic fibrosis. As more children were referred to me for investigation by our team, there was an increasing interest in paediatric gastrointestinal problems at Seacroft and St James’s. Subsequently this led to increasing cooperation with Professor Losowsky’s University Department of Medicine at St James’s University Hospital where the main research interests were gastroenterology and nutrition.

In 1975 – the first publication on CF from Seacroft

John Davies

In the late Sixties Dr. Beat Hadorn, a paediatrician from Bern, had published a method for performing pancreozymin-secretin stimulated pancreatic function tests using a triple lumen tube (Hadorn et al, 1968). I obtained a supply of these tubes and our senior registrar at the time, Dr. John Davies, developed pancreatic function tests at Seacroft with the help of our consultant radiologist Dr. Sydney Smith. For the pancreatic function test the patient is fasted, heavily sedated has an intravenous line inserted and the triple lumen tube sited under x-ray guidance. After an injection of pancreozymin two 10-minute periods of juice rich in enzymes and bile are obtained. After secretin four 10-minute periods of juice rich in bicarbonate is obtained. In CF the juice is very scanty and low in enzymes and particularly low in bicarbonate.

The tests proved useful and interesting but were too involved and invasive for routine use; but they did contribute significantly to the first publication on CF from Seacroft in 1975 by the Drs. Jim Sarsfield (figure) and John Davies (figure). The tests provided supporting evidence that two children with negative sweat tests, but the typical clinical features of CF did have cystic fibrosis (Sarsfield & Davies, 1975). The rare occurrence of a normal sweat test in an individual with clinical features of CF has been confirmed in subsequent publications. Subsequently, we had another child who had gross malabsorption and the typical clinical features of CF but a repeatedly normal sweat and a normal jejunal biopsy. The sweat test in this child eventually became positive and she died of CF at the age of 25 years.

– Sarsfield JK, Davies JM. Negative sweat tests and cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 1975; 50:463-466. [PubMed]

1975 We start neonatal CF screening St Mary’s Maternity Hospital, Bramley after discussion with Miss Little, the Matron

St Mary’s Maternity Hospital, Bramley, Leeds

St Mary’s Maternity Hospital in Leeds was initially the Bramley Union Workhouse and which opened in 1871. By the time I was appointed a consultant in 1968 to provide paediatric cover there it had become the largest maternity unit in the city but with slightly less privileged clientele than the other two units at the city’s main teaching hospitals; a significant proportion of our 3000 admissions were for social reasons. It was slightly “out on a limb” and not really ideal for acute obstetrics but the staff were very dedicated and there were plenty of babies and an excellent special care baby unit sister, Doreen Burton.

My personal interest in newborn screening had developed some years previously during the mid-Sixties when I was lecturer in paediatrics with Professor Craig at the Leeds Maternity Hospital; this eventually led to an MD thesis in 1968 on the incidence of neonatal urinary tract infection and various other related publications from the thesis.

– Littlewood JM. Asymptomatic bacteriuria Br Med J. 1969 Aug 16;3(5667):416. PMID: 5797794

– Littlewood JM, Kite P, Kite BA. Incidence of neonatal urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 1969 Oct; 44(237):617-20. PMID: 4981204

– Littlewood JM, Hunter I, Payne RB, Miles DW. Placental transfer of an IgG paraprotein associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Br Med J. 1970 Oct 10;4(5727):94-5. PMID: 5471777

– Littlewood JM. White cells and bacteria in voided urine of healthy newborns. Arch Dis Child. 1971 Apr;46(246):167-72. PMID: 5576025

– Littlewood JM. 66 infants with urinary tract infection in first month of life. Arch Dis Child. 1972 Apr;47(252):218-26. PMID: 5023470

– Littlewood JM. Letter: The prevalence of bacteriuria in full-term and premature newborn infants. J Pediatr. 1973 Nov; 83(5):888-9. pMID: 4742588

– Davies JM, Gibson GL, Littlewood JM, Meadow SR. Prevalence of bacteriuria in infants and preschool children. Lancet. 1974 Jul 6;2(7871):7-10. PMID: 4134405

– Meadow SR, Davies JM, Gibson GL, Littlewood JM. Letter: Urinary tract infection in children of preschool age. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Jul; 50 (7):578. No abstract available. PMID: 116707

– Littlewood JM. Neonatal screening: the present position. Midwives Chron. 1977 May;90(1072):91-3. No abstract available. PMID: 586487

– Ghosh SK, Littlewood JM, Goddard D, Steel AE. Stool microscopy in screening for steatorrhoea. J Clin Pathol 1977 Aug;30(8):749-53. PMID: 599187

– Littlewood JM, Jacobs SI, Ramsden CH. Comparison between microscopical examination of unstained deposits of urine and quantitative culture. Arch Dis Child. 1977 Nov;52 (11):894-6. PMID: 339849

Although from 1968 my role as a general paediatrician included the paediatric supervision of the 3000 infants born each year at St Mary’s, neonatology in the days before ventilation was less demanding than today. In the mid-Seventies, after discussion with Miss Little, the Matron, it was agreed we introduce the recently available BM Meconium screening test for cystic fibrosis.

The BM meconium test depends on the abnormally high protein content of the meconium of infants with cystic fibrosis. Although an unusual protein content in the

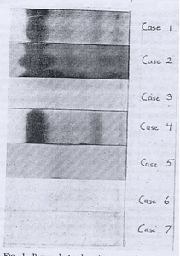

meconium of infants with meconium ileus had been described by a number of authors, the study of Wiser (Wiser WC et al. 1964) showed that the meconium from all infants with CF also had an increased protein content. The authors suggested that perhaps this could be “used in a predictive manner” i.e. for neonatal screening. In Wiser’s study (figure) using immunoelectrophoresis, the meconium from five infants with a history of CF was examined for increased protein. Three infants with CF (1,2,4) had obviously raised albumin levels, which did not occur in the two unaffected at risk cystic fibrosis infants (3,5) or in two healthy controls (6,7).

Wiser WC, Beier FR. Albumin in the meconium of infants with cystic fibrosis : a preliminary report. Pedaitrics 1964 Jan; 33:115-9.

Later Schutt & Isles (1968) from Bristol showed that the increased meconium albumin could be recognised very simply by using the Albustix dipstick test designed for testing urine for albumin. A few drops of water mixed with a small amount of meconium was placed on a tile and an Albustix applied to the edge of the drop when it would turn blue if there was excess albumin (figure of urine Albustix). This method eventually formed the basis of the commercially available Boehringer Mannheim test (BM test) used with variable success in a number of neonatal CF screening studies in the Seventies (Stephan et al 1975; Ryley et al 1979; Evans et al, 1983).

– Schutt WH, Isles TE. Protein in meconium from meconium ileus. Arch Dis Child. 1968 Apr;43(228):178–181.

– Stephan U, Busch EW, Kollberg H, Hellsing K. Cystic fibrosis detection by means of a test-strip. Pediatrics. 1975 Jan; 55(1):35–38

– Ryley HC, Neale LM, Brogan TD, Bray PT. Screening for cystic fibrosis by analysis of meconium for albumin and protease inhibitors. Clin Chim Acta. 1975 Oct 15;64(2):117–125.

Undeterred by the lack of enthusiasm displayed by my two senior consultant paediatric colleagues at the other two Leeds maternity units, in 1975, after discussions with Miss Little, the very supportive Matron, we introduced the BM Test at St Mary’s Maternity Hospital.

However, after a few weeks on my regular visits to the maternity wards I frequently noted little plastic pots containing small quantities of meconium, some even growing mould! It soon became obvious that even this simple strip test was asking too much of the overworked but always willing midwives! Fortunately Dr. Robert Evans, at the time the consultant biochemist at St James University Hospital, across the city, agreed to perform our BM tests in his laboratory on specimens of meconium collected into tiny pots by the midwives from all infants. This system worked very well and in 1981 we reported favourable results since we started BM screening in 1975 (Evans et al, 1981). Although by 1981 most paediatricians had either never started or by this time rejected the BM test for neonatal CF screening, at St Mary’s Maternity Hospital in East Leeds the test had become an effective and established routine for identifying CF infants in the newborn period.

We had more success with the BM Test than in some other places and our false negative rate was only 12% – but as described we found, as had the people in Veneto, Italy that the test must to be carried out in the laboratory with proper quality control and not on the wards by the midwives who, we soon realised, were far too busy. This was undoubtedly the reason other studies had failed.

– Evans RT, Little AJ, Steel AE, Littlewood JM. Satisfactory screening for cystic fibrosis with the BM meconium procedure. J Clin Pathol 1981 Aug; 34(8):911-3.

Neonatal CF screening becomes established at St Mary’s, Leeds

Although others were reporting the BM test was unsatisfactory (Stephan et al 1975; Ryley et al 1979; Prosser et al 1974), it slowly became apparent that we were obtaining reasonable results, but only because the test was performed in the laboratory with proper quality control which was not the case elsewhere. The other important reason many paediatricians were unenthusiastic about neonatal CF screening was they did not believe early diagnosis affected the long-term outlook; of course this was true if early diagnosis was not accompanied by early effective treatment. It is true that in the Seventies and Eighties there was no published evidence that early diagnosis through neonatal screening and the start of treatment available at the time, improved the eventual outlook for infants with CF. Indeed it was not until 2001 that definite generally accepted evidence of long term benefit on growth was published from Phillip Farrell of Wisconsin (Farrell et al, 2001). In fact, a large study from Wales and West Midlands in the Eighties, funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Trust had failed to show an advantage for the screened infants (Chatfield et al 1991). This was almost certainly due to the fact that many of the CF infants identified did not receive specialist CF centre care but were treated at a number of local hospitals by the local paediatrician .

– Prosser R, Owen H, Bull F, Parry B, Smerkinich J, Goodwin HA, Dathan J. Screening for cystic fibrosis by examination of meconium. Arch Dis Child. 1974 Aug;49(8):597–601.

– Chatfield S, Owen G, Ryley HC, Williams J, Alfaham M, Goodchild MC, Weller P. Neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis in Wales and the West Midlands: clinical assessment after five years of screening. Arch Dis Child. 1991 Jan;66(1 Spec No):29-33.

– Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Rock MJ, Laxova A, Zeng L, Lai HC, Hoffman G, Laessig RH, Splaingard ML. Early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening prevents severe malnutrition and improves long-term growth. Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Study Group. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan; 107(1):1-13.

So despite the lack of national and local enthusiasm (including both consultant paediatricians at the other two maternity units in Leeds!) neonatal CF screening became an established routine in my own neonatal unit at St Mary’s, Bramley. In the first 5 years from 1975, 15,734 newborns were screened; a positive BM Test was obtained in 130 of whom 7 had CF – this was the expected incidence of 1/2243 live births. Also the false positive rate was an acceptable 0.83% (Evans et al, 1981).

– Evans RT, Little AJ, Steel AE, Littlewood JM. Satisfactory screening for cystic fibrosis with the BM meconium procedure. J Clin Pathol 1981;34(8):911-3.

Periodically during this first five years from 1975 when we would identify a newborn with CF and it would seem sensible to start treatment with a regular anti-staphylococcal antibiotic (cloxacillin) as recommended by Dr. David Lawson one of the UK.’s few leading experts at the time, and also to start gentle physiotherapy, pancreatic enzymes and vitamin supplements.

We used the BM test for the next 20 years in the eastern half of Leeds both at St Mary’s and later also at the smaller St James’s University Hospital maternity unit when the two units merged and moved into new accommodation at St James’s in 1979. Dr. Ian Forsythe, the consultant paediatrician in charge of the St James’s neonatal unit before we merged, did not approve and although he reluctantly agreed to introduce the test, he chronically voiced his opposition to the CF screening at every opportunity! We eventually replaced the BM test with the immunoreactive trypsin heel prick test (IRT) in 1995 at which time the neonatal unit at the Leeds General Infirmary eventually and reluctantly agreed to introduce neonatal CF screening.

Gianni Mastella

So there has been continuous neonatal CF screening in East Leeds first at St Mary’s and later at St James’s since 1975. Only one area of Italy had been screening continuously for longer having started in 1974 by Gianni Mastella (Mastella 1981).

– Mastella G1, Zanolla L, Castellani C, Altieri S, Furnari M, Giglio L, et al. Neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis: long-term clinical balance. Pancreatology. 2001;1(5):531-7.

1976 A monthly afternoon clinic at Seacroft is devoted to children with CF – the start of the “CF Clinic” and the Leeds CF Service

In 1975/6, soon after neonatal CF screening started at St Mary’s, I started to follow-up the first few screened CF infants, and with the agreement of the nursing staff, we set aside a monthly Monday afternoon paediatric clinic session for our few CF children at Seacroft. The majority of the children’s medical beds were situated there and it was my base where I had a secretary, office and a major clinical commitment. In this CF clinic venture I had the enthusiastic support of the nurse in charge of Seacroft outpatients (Sister Moriarty), the paediatric physiotherapist (Miss Jenkins) and the paediatric dietitian. June Wilson, was Sister on one of the paediatric wards where all my beds were situated.

Landmark Seacroft Hospital water tower

Small outpatient block where first monthly CF clinics were held

Sister June Wilson’s nursing staff were also becoming increasingly interested and knowledgeable about CF as more children with condition came to the ward either for investigations such as sweat tests by Mr Steel or for admission and treatment. The importance of the support and interest of staff with special expertise cannot be over emphasised and is certainly appreciated by the parents.

Paediatric colleagues gradually became aware of our new Monday afternoon “CF clinic” and of my increasing interest in the condition. When the Professor of Paediatrics, Dick Smithells, informed all paediatricians in the Leeds Region of the special clinics in his department at the General Infirmary, I took the opportunity to inform our regional colleagues of my CF clinic and other specialist clinics at Seacroft! By the late Seventies I was also running special clinics sessions designated for gastroenterology, asthma, diabetes and urinary tract infections (this with Professor Roy Meadow and Mr. Bob Williams, a distinguished local urologist). This may seem rather excessive but I was now an established and very busy Leeds consultant and fortunate to be receiving many referrals. It seemed reasonable to assemble children with certain chronic problems into special clinics where one could concentrate the mind on their problems and they could be seen and discussed with various expert colleagues.

I hope it would not be immodest to observe that an undoubted highly relevant factor in the development of our Leeds CF service from 1980 was my 20 years broad “hands on” experience of general paediatrics.

Wide paediatric experience is so important when dealing with children with CF, a condition that seems to affect every system in the body. In the early 20th Century Sir William Osler used to teach “Know syphilis…and all other things clinical will be added unto you”. In the Sixties Sir Stanley Davidson suggested that, as we passed from the era of infection to metabolic disorders, Osler’s dictum might well be changed to “Know diabetes……..”. Now, in the era of genetic diseases, back in 1983, I suggested – “Know cystic fibrosis and all other things clinical will be added unto you” may be even more appropriate, so varied and complex are the problems encountered in people with the condition? (from Advanced Medicine. 1983 Eds. Losowsky MS, Bolton RP. Royal College of Physicians, London 1983).

The advantages of treating many patients with the same condition

A further wise observation of Sir William Osler’s is relevant in the context of cystic fibrosis –“Medicine is to be learned by experience; and is not an inheritance; it cannot be revealed. Learn to see, learn to hear, learn to feel, learn to smell, and know that by practice alone can you become expert”.

Hence my enthusiasm for seeing as many patients as possible in clinics where one could improve knowledge of the condition and observe where improvements and changes were needed.

To expand on and reinforce this statement, I will mention the only three really original clinical observations I have made during my career – all were the direct result of experience gained from personally seeing, investigating and treating many patients with a particular condition or complication. I will discuss these in more detail elsewhere (in the Reflections section of www.jimlittlewood.com) but briefly they are the following –

1. That inhaled colomycin would eradicate a new growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in children with CF – contrary to previous teaching. – Littlewood JM, Miller MG, Ghoneim AT, Ramsden CH Nebulised colomycin for early pseudomonas colonisation in cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1985 Apr 13;1(8433):865.

2. That inhaled corticosteroids (Becotide) could impair the growth of some children with asthma. – Littlewood JM, Johnson AW, Edwards PA, Littlewood AE. Growth retardation in asthmatic children treated with inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate. Lancet. 1988 Jan 16;1(8577):115-6.

3. That coeliac disease in the Yorkshire region was disappearing. – Littlewood JM, Crollick AV, Richards IDG. Childhood coeliac disease is disappearing. Lancet 1980 Dec 20/27:1359.

All three original observations were the result of accumulating considerable experience derived from carefully following, investigating or treating many patients with a particular condition. The importance of significant patient numbers, careful follow-up and continuity of professional involvement are of great importance – hence my deep unwavering commitment to CF Centre Care for all people with the condition. The care and dedication of the nurses in the paediatric clinics in their accurate weighing and measuring of the children at every clinic attendance was of great importance in the inhaled steroid observation.

To return to the development of the Leeds CF service.

During the late Seventies a few general paediatricians transferred some of their patients to our small monthly CF clinic at Seacroft and then to St James’s when my clinics moved there in 1980. In some cases the children were referred reluctantly by their paediatricians and then only when they were obviously deteriorating. Some colleagues, it must be said including our own Professor Dick Smithells and the Leeds NHS consultant Dr. Ian Forsythe, did not transfer their few CF children for some years; they both openly and repeatedly questioned both the need for a specialised CF Clinic and for neonatal CF screening. This attitude was not unusual among older paediatricians during the Eighties as evidenced by the British Paediatric Association Council’s rejection of their own CF Working Party’s recommendation that all children with CF should be known to and have some contact with a CF centre!

with their new baby in 2002

Also the UK National Screening Committee’s repeated refusal to recommend national neonatal CF screening was disappointing and eventually shown to be misguided. Even when it was approved by Yvette Cooper, the then Health Minister, on behalf the government in 2001 after strong pressure from the CF Trust and against the National Screening Committee’s advice. However, common sense won the day thanks to Yvette Cooper who happened to be pregnant (which perhaps helped our case!) when Rosie Barnes of the CF Trust and I visited her at the Ministry of Health to put the case for screening.

1978. The first CF research study from Leeds

At that time, when we had some 25 children attending our monthly CF clinic at Seacroft, research collaboration began with my friend and colleague Professor Monty Losowsky, Professor of Medicine at St James’s University Hospital. His academic department had a distinguished record of research particularly into nutrition and various aspects of gastroenterology.

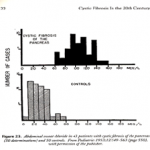

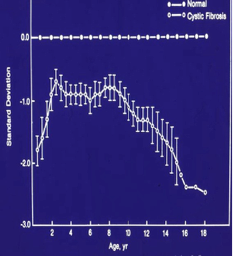

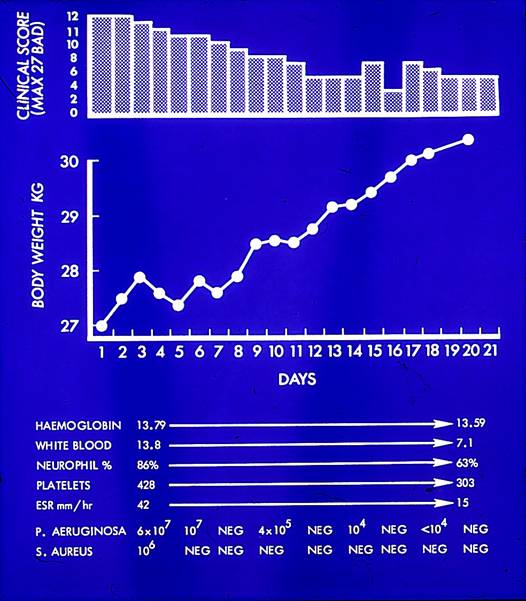

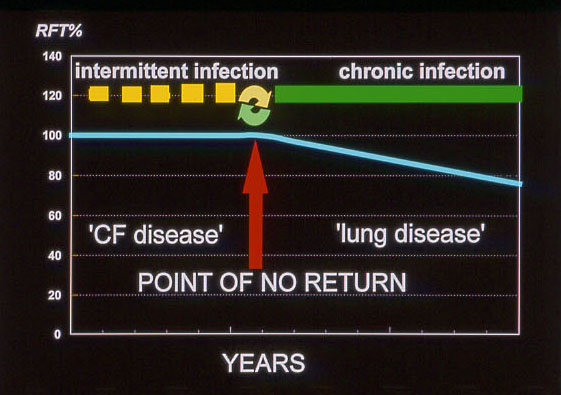

Inevitable decline in nutritional state Berry et al 1975

I asked Monty if he and his colleagues would help us investigate the nutritional state of our CF children, as maintaining a reasonable nutritional state was a major problem. As the children’s respiratory infection progressed relentlessly it was virtually impossible to maintain a reasonable nutritional state as evidenced in the figure (Berry et al, 1975). Monty Losowsky agreed to join forces and with Dr. Jerry Kelleher, the senior biochemist in his department, we planned and started the first of many collaborative research projects with members of the Department of Medicine at St James’s.

– Berry HK, Kellog FW, Hunt MM, Ingberg RL, Richter L, Gutjahr C. Dietary supplement and nutrition in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Dis Child 1975; 129:165-171. [PubMed]

In our first study, carried out in the two years before we moved two miles down the road from Seacroft to St James’s, we performed an evaluation of the present nutritional state of our patients with particular reference to the vitamin status – a particular interest of Dr. Jerry Kelleher’s, the senior biochemist in Monty’s department at St James’s. Also, we enlisted a few additional children with CF attending the clinics of interested paediatric colleagues, such as Dr Paddy Clarke of Harrogate and Dr Michael Buchanan in Leeds, to reach a total of 36 children with CF and 21 age-matched non-CF children as controls. When the children attended the monthly CF clinic at Seacroft I would take a venous blood specimen and Jerry Kelleher’s wife would deliver it to his laboratory at St James’s down the road.

The parents were very enthusiastic, relieved that at last some research was underway and they were very supportive – as we always found them to be subsequently with all our research studies. I was very pleased and grateful to be cooperating with such a very professional team of experts who were more experienced than myself or any of our team in research of this type. The study was supported by a grant from the West Riding Medical Research Trust obtained by Professor Losowsky.

Continuing cooperation with members of Monty Losowsky’s Department of Medicine at St James’s University Hospital, particularly Dr Jerry Kelleher and his technician Mr Mike Walters, over nearly 20 years, on numerous subsequent combined projects, was undoubtedly one of the major factors responsible for the success and growth of our Leeds CF service.

- Prof. Monty Losowsky

- Dr Jerry Kelleher

- Mr Mike Walters

The summary of this first study published in 1981

– Congdon PJ, Bruce G, Rothburn MM, Clarke PC, Littlewood JM, Kelleher J, Losowsky MS. Vitamin status in treated patients with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1981 Sep; 56(9):708-14. PMID: 729487430

The late Dr. Peter Congdon was our Senior Registrar at the time. He played a major part in coordinating this and other studies during his time with me. He also shouldered much of the work of the neonatal unit at St James’s and was eventually appointed consultant neonatologist at the Leeds General Infirmary. It was tragic that he died from carcinoma after only a few years in that post.

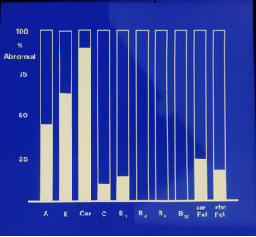

In the study the water-soluble (B1, B2, B6, C, folic acid) and fat-soluble vitamin (A, carotene, E, and D) status of the 36 patients with cystic fibrosis was assessed and compared with a control group of 21 age-matched non-CF children. Twenty-seven of the patients were receiving vitamin

Vitamin status of the 36 CF patients

supplements (except for folic acid and vitamin E) at the time of investigation. Vitamin B1, B2, and B6 status was adequate in all patients (figure), and there was little evidence of folic acid deficiency. Vitamin C stores might not have been adequate in some of these patients, despite daily supplements with 50 mg of the vitamin. Steatorrhoea, often severe, was present in most of the children. Only 4 of 24 patients had a normal fecal fat (<17.6mmol or <5 g per 24hrs) despite pancreatic supplements. Steatorrhoea was often severe: 10 patients had values greater than 100mmol (28.4g)/24hrs and 17 had values greater than 50mmol (14.2g)/24Hrs. Serum carotene and vitamin E concentrations were low in over 90% of patients and were related to the severity of steatorrhoea. Vitamin A was low in over 40% of the patients despite daily vitamin supplements of 4000 IU and correlated with the serum retinol-binding protein level. Serum 25-OH cholecalciferol was low in some patients whether or not they were receiving a daily supplement of 400 IU vitamin D and correlated with the serum retinol-binding protein level. Except for serum vitamin A, which was lowest in patients with the poorest clinical grading, the other vitamins were not influenced by the clinical grade of the patients

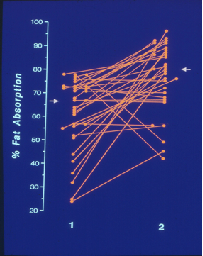

(Figure left) The severe steatorrhoea, which was present in most of the children, was considerably improved following adjustment to the pancreatic replacement therapy either by increasing the dose or the timing

(Figure right) In a subsequent short-term supplementation trial (figure right) with water-miscible preparations of vitamin A (4000IU) and E (50mg) in 14 patients, the serum levels vitamin E and 4000 IU vitamin A responded well to 2 weeks of treatment

Dr. Kelleher’s laboratory with Mr. Mike Walters performing fecal fat estimations (available in very few hospitals), plasma vitamin levels and subsequently many other investigations not available in most hospitals, was central to much of our research in the years that followed.

So vitamin status and intestinal malabsorption both improved. What other areas could be improved?

Fat-soluble vitamin status and intestinal malabsorption were two important areas where treatment could be much improved in many patients . Certainly as far as these two vitamins and the pancreatic enzymes were concerned, it was now obvious that in the late Seventies many of our CF children were receiving suboptimal treatment.

It was at this stage that I decided to see what other areas of management could be improved. It was the start of our “Comprehensive CF Assessments” along the lines that Douglas Crozier had recommended in 1974 i.e. to “perform a complete assessment of the patient” and then make “continuing attempts to obtain normal bodily function and maintain it”. Practical support in the form of dedicated CF staff funded by the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust was crucial.

Ron Tucker OBE

During the Seventies and early Eighties we received a great deal of encouragement to develop our embryonic CF service from Mr. Ron Tucker OBE the inspirational Executive Director of the UK CF Research Trust. Ron realised how poor the care of CF was in most UK hospitals at that time. With his encouragement, by the mid-70s I became involved with the local West Riding Branch of the Cystic Fibrosis Research Trust, first as Chairman and later as Honorary Medical Advisor when the first Medical Advisor, Dr. Douglas Pickup of Pontefract, retired. I also accepted all invitations to talk about and publicise CF to local interest groups, Roundtables, Ladies Circle’s, Rotary Clubs, Working Men’s clubs, school assemblies – encouraged by Ron Tucker. Few people had heard of the condition even in the Eighties (for example “We thank Dr. Littlewood for coming to talk to us about Cystic Fibrositis”).

So we made a major effort to increase awareness of CF in the Leeds Region by whatever means we could. It was a definite advantage that I was by that time relatively well known in Leeds and beyond having been a busy consultant general paediatrican for the previous decade and frequently dealing with children from outside Leeds. I accepted every invitation to talk to groups, talk to schools , receive cheques on behalf of the CF Trust at functions. The CF Research Trust (i.e. essentially thanks to Ron Tucker) repaid my effortsby funding our first full-time CF Research Fellow in 1983, Dr. Mike Miller (the first such appointment in the UK) and our first CF Nurse Specialist, Teresa Robinson (only the second in the UK the first being at the Royal Brompton in London) with funds from the Joseph Levy Foundation. Joe Levy, a wealthy London businessman, was the Chairman of the Cystic Fibrosis Trust for the first 20 years, one of the founders in 1964 and a massive financial supporter of the charity

- Teresa Robinson

- Mike Miller

- Joe Levy CBE

Mike Miller at the computer in my office with John Gilbert (our second CF Research Fellow) and Ann Littlewood (CF Research Nurse)

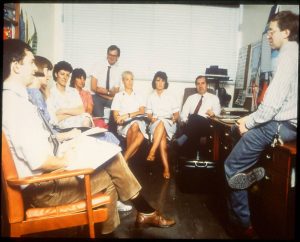

So by the early Eighties we had the makings of a dedicated CF team – an absolute essential for developing an effective CF service.

1980. Our paediatric clinics and beds move to St James’s University Hospital

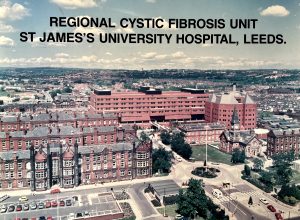

St James’s University Hospital in the Eighties

In 1980 my clinical facilities – in-patients beds, outpatients, office and secretaries moved down the road from Seacroft to St James’s University Hospital – at that time Europe’s largest general hospital.

The move to St James’s allowed us to involve many more of our clinical, laboratory, radiological and colleagues also the nurses, physiotherapists, dietitians and social workers who formed the basis of the CF team.

To have an experienced paediatric registrar and staff nurse totally devoted to CF in the hospital was a major step forward in developing the CF service. They Mike and Teresa became known to other members of the hospital staff, patients and parents and became the first point of contact in the hospital of all matters relating to CF. Mike Miller was with us for 2 years and Teresa Robinson was permanent so children, families and other staff in the hospital soon knew them well. The continuity of involvement was very important.

From 1983, during their 2-year appointments, our subsequent Clinical CF Research Fellows (figure) combined with members of Monty Losowsky’s department and others in the hospital, on aspects of nutrition, energy utilisation, intestinal malabsorption and intestinal pH.

Some of Leeds CF Research Fellows (L to R) Eduardo Moya, Ian Bowler, Sally Connelly, Eddie Simmonds, Mike Miller, Kevin Southern, John Gilbert at My retirement in 1997

Most of the CF Research Fellows in the photo all eventually continued treating children with CF and building CF Clinics when they eventually became consultants. Eduardo Moya – Bradford, Sally Connelly – Sheffield, Ian Bowler – Newport, Eddie Simmonds – Coventry, Mike Miller – Huddersfield, Kevin Southern – Liverpool, John Gilbert – Macclesfield, Sunita Seal – Bradford.

The sense of urgency to improve matters regarding the poor outlook for the children with CF resulted in many of our NHS general paediatric junior staff wishing to be involved in CF research often combining with the CF Nurse, CF Research Fellow and other colleagues in the hospital. Therefore many of my NHS general paediatric staff (Senior House Officers, registrars and senior registrars) combined with our CF staff and/or members of Monty Losowsky’s department on a variety of research projects on both CF and non-CF subjects. There was also important input from a series of highly skilled and enthusiastic lecturers in the Department of Medicine prepared to collaborate with specific research projects involving our rapidly growing CF population. In fact, eventually there were few consultants and staff in St James’s who at one time or another did not apply their expertise to some problem relating to cystic fibrosis!

Many of the other NHS junior staff who worked with us at St James’s as either SHO, Registrar or Senior Registrar level were involved in clinical research and subsequently in treating CF patients.

David Beverley – Consultant in York with a CF clinic; Jim Sarsfield consultant in Harrogate with a CF clinic; Andy Mellon consultant in Sunderland with a CF clinic; Iolo Doull consult in Cardiff with regional CF service; Steve Conway became director of Paediatric and Adult CF service in Leeds; Keith Brownlee consultant at St James’s and eventually senior position with the UK CF Trust; Tim Lee became Director of the Leeds Regional Paediatric CF service; Alison Essex-Cater consultant paediatrician in Northallerton with a CF clinic; Mike Mahony built up major CF clinic in Limerick; John Davies consultant in Grimsby with a CF clinic.

- David Beverley

- Jim Sarsfield

- Andy Mellon

- Iolo Doull

- Steve Conway

- Keith Brownlee

- Tim Lee author’s photo

- Alison Essex-Cater

- Mike Mahony

- John Davies

1980 The North American CF Conference in Toronto

So we had now moved to St James’s and in 1980 I travelled to Toronto to present the results of our first nutritional Seacroft study at the N. American CF Conference. This was the first presentation from our CF clinic at a major CF Conference and also my first spoken presentation at a major CF conference. We also had a poster describing our neonatal CF screening results – the data later published in Robert Evans’s paper in 1981.

This was the start of a very steep learning curve with regard to CF for all of us concerned with our CF unit in Leeds; undoubtedly attendance at this conference had a major influence on my approach to treating children with CF at Seacroft and St James’s University Hospital.

Douglas Crozier is presenting the “Breath of Life Award” to Maureen McChesney (Lavergne) in February 1970. (Reproduced with permission of the family).

Toronto Children’s Hospital in 1980

“Cystic fibrosis – a not so fatal disease” (Crozier, 1974).

This paper gives an idea of treatment at the Toronto CF clinic in the early Seventies. Crozier stated – “Success of treatment will depend on a complete assessment of the patient and then continuing attempts to obtain normal bodily function and maintain it”.

He described how he advised his patients to abandon the traditional low fat diet and use very high doses of pancreatic enzymes (up to 100 Cotazym capsules per day). Crozier believed – “to deprive a child with cystic fibrosis, who usually has very little subcutaneous fat, of this important nutrient seems ridiculous”.

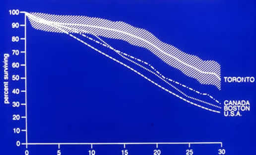

Superior survival of Toronto patients from Corrie et al 1988

The resulting superior nutritional state of the Toronto patients, almost certainly related to Crozier’s early treatment, is believed to be the main reason for their significantly better survival. A classic and oft-quoted study compared survival curves between 1972-1981 of 499 Boston patients and 534 Toronto patients (figure). The Toronto patients were taller and heavier than the Boston patients although they had similar respiratory function. Median age of survival in Boston was 21 years and in Toronto 30 years with divergence occurring from the age of 10 years. The authors concluded “The differences in growth and survival in these two patient groups, with very similar age specific pulmonary function, suggest further examination of nutritional guidance and intervention in CF especially regarding the traditional restriction of dietary fat” (Corey et al, 1988).

– 1988 Corey M, McLaughlin FJ, Williams M, Levison H. A comparison of survival growth and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis in Boston and Toronto. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41:588-591. [PubMed]

In 1973 428 people with CF were attending the Toronto clinic of whom 92 (21.4%) were 16 years or older – this was quite remarkable for at that time survival into adult life in the UK was very unusual.

More recently, in 2017, it has been reported that survival of adults with CF in Canada (48.5 years) exceeds that of those in the USA by 10 years (36.8 years) (Stephenson et al 2017). The authors concluded the differences in cystic fibrosis survival between Canada and the United States persisted after adjustment for risk factors associated with survival, except for private-insurance status among U.S. patients. Differential access to transplantation, increased post-transplant survival, and differences in health care systems may, in part, explain the Canadian survival advantage. However, it is possible that the early nutritional management of these Canadian patients also may have been a significant factor.

– Stephenson AL, Sykes J, Stanojevic S, Quon BS, Marshall BC, Petren K, Ostrenga J, Fink AK, Elbert A, Goss CH. Survival Comparison of Patients With Cystic Fibrosis in Canada and the United States: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M16-0858. [Epub ahead of print]

Dr Mary Corrie with Ann Littlewood

Dr. Mary Corey has been CF Research Scientist at the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children since the Seventies and created the comprehensive Toronto CF database. She is co-author in over 150 publications from Toronto many on various aspects of cystic fibrosis. In 2007 she was co-Chairman of the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference programme committee

Many N. American “CF Teams” attended the 1980 Toronto conference

In relation to CF centres, the other surprise for me at the 1980 Toronto conference was the presence of so many nurses, physiotherapists, dietitians and psychologists/social workers at the meeting. At that time there was only one specialist CF nurse in the UK at the Royal Brompton in London and there were few specialist nurses apart from Special Care Baby Unit Nurses attached to premature baby units. At that time it would have been unusual for UK nurses or allied health professionals to attend a major international medical conference.

The care most of our CF children were receiving in the Seventies was quite obviously below the standard of that received by many children fortunate enough to be attending one of the major N. American centres. Although, as Ron Tucker told me many times in this context, the standards did vary widely between clinics in the USA. In the UK very few CF children attended such clinics where care was of such a high standard as that provided by Drs. Winifred Young, Margaret Mearns, Archie Norman and David Lawson in their London clinics and Prof. Charlotte Anderson in Birmingham. Most UK children did not attend such clinics and most died in childhood, the dreadful prognosis being accepted by many parents and professionals as inevitable.

Warren Warwick

As far back as the early Sixties Leroy Matthews and Carl Doershuk (Matthews & Doershuk, 1964; Doershuk et al, 1964; Doershuk et al, 1964) at the Cleveland Centre were already reporting improved results that some paediatricians in N. America found hard to believe. Veteran CF physician Dr. Warren Warwick of Minnesota wrote of Leroy Matthews – “Leroy Matthews, the greatest genius CF has seen, single handedly established the value of Comprehensive Treatment, laid the ground work for Pediatric Pulmonology, and led the CF Centres as well as planning and directing excellent research. He made only two mistakes. He allowed his “Comprehensive Treatment” plan to be equated with “mist tent therapy” so when the mist tent was discredited many also felt the Comprehensive Care Program was discredited”. The other was he tried too hard to control his own diabetes.

In the context of the excellent Cleveland results, Warren Warwick considered “one of the factors that led to the establishment of a ten year annual grant (to Warwick for his database) from the CF Foundation was the desire of some of the early leaders in CF (connected to the CF Foundation) to prove that Leroy Matthews was a fraud in claiming to have reduced the annual mortality of CF by some tenfold”. When Warwick’s Patient Registry data showed that the annual mortality was indeed less than 2% per year the same doubters engineered a conference in Philadelphia to show that the statistical studies done in Minnesota were incorrect. However, the opinion of a leading life insurance actuary was sought and he found the figures to be correct ! (Warwick, 2001).

– Warren Warwick in Doershuk CF (ed). Cystic fibrosis in the 20th Century. AM Publishing, Cleveland 2001:319.

– Matthews LW, Doershuk CF, Wise M, Eddy G, Nudelman H, Spector S. A therapeutic regimen for patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 1964; 65:558-575.

– Doershuk CF, Matthews LW, Tucker AS, Nudelman H, Eddy G, Wise M, Spector S. A 5-year clinical evaluation of a therapeutic program for patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 1964; 65:677-93.

– Doershuk CF, Matthews LW, Tucker A, Spector S. Evaluation of a prophylactic and therapeutic program for patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 1965; 36:675-688.

May 1980. We start “Comprehensive CF Assessments” at St James’s in Leeds

In view of the suboptimal treatment our first study in the late Seventies had revealed, and on the basis of Crozier’s recommendation to “perform a complete assessment of the patient” and then “continuing attempts to obtain normal bodily function and maintain it”, in May 1980, as soon as I returned to Leeds from the Toronto meeting, with the help of a few colleagues at St James’s, we started regular Comprehensive CF Assessments (often referred to as “Assessments” in the following text).

During 1980 over the next year all our CF children had Assessments, both children from our own clinic and any referred from other consultants, to determine if there was any way we could improve their condition or treatment. These Assessments involved all aspects of the child’s physical condition and treatment (details below). I suspect in these days of Cochrane Systematic Reviews and evidence-based medicine, CF Assessments would not have been funded as, at that stage, we had absolutely no idea what such detailed and expensive Assessments would show or if acting on the knowledge so gained would result in long-term benefit for the patient. What is the evidence to correcting a low vitamin E level will have a significantly favourable effect on the patient? We didn’t know – but common sense suggested that it seems reasonable to correct it. Fortunately, as I will describe, the frequent major changes in management introduced as a result of these Assessments did have a profound long term effect on the health and outlook for many children with CF. Over the years such annual Assessments eventually became an established and recommended part of management were adopted by most CF centres – the “Annual MOT” using the analogy of the motorcar. Undoubtedly Leeds led the way in this practice by many years.

The concept of dedicated specialist CF Teams at CF centres appeared to be well established in some parts of N. America by 1980. The concept had been encouraged and sponsored by the CF Foundation since the early Sixties following the excellent results from Leroy Matthews and Carl Doershuk.

May 1981. We offer Comprehensive CF Assessments to consultant paediatric colleagues in the Yorkshire Region for their CF patients.

The first twelve month’s CF Assessments on our own CF patients from May 1980, started as soon as I returned from Canada; they revealed numerous areas where our management could be improved by more effective use of already available treatments.

In 1981 the obvious importance of these disappointing results on our first 20 or so patients prompted me to write to all paediatric consultants in the Yorkshire Region (population 3.6 million), many of whom I had known for a number of years, describing the disturbing results on our own CF patients. I described how we had discovered many areas where treatment could be improved. So in the light of these findings, I offered for our team to carry out CF Assessments on their patients. I made it clear from the outset we would not “take over” their patients – merely carry out a detailed assessment of every aspect of their treatment and condition, after which I would return them with a full report and suggestions for any changes in management considered appropriate.

This would not have been possible in 2017 in the NHS, due to funding problems, but in 1981 there was no restriction on referring patients from one hospital to another from any part of the country – no question of funding issues – that was to come later! In fact, cost did not figure high on our reckoning at that time although it gradually became a very significant factor.

This freedom to accept referrals from elsewhere was obviously a major factor facilitating the development of our regional CF service.

1981 There were soon referrals from around the Yorkshire Region and beyond

Referrals of new patients to the Leeds

Understandably the first children referred from elsewhere were those experiencing particular problems and whose condition was causing concern to their parents and the local paediatrician. Also Ron Tucker, Director of the CF Trust, had encouraged other families to ask for a referral to my clinic at St James’s if they were concerned about the treatment they were receiving at their local hospital.

Thus, by 1982, we were providing a CF Assessment Service not only for our own Leeds patients but also for those referred by paediatric consultants from other hospitals in the region. Despite my best intentions not to “take over” the children, approximately 10% of those referred were in such poor condition that they were admitted at once to our ward at St James’s for intensive physiotherapy, intravenous antibiotics and nutritional rehabilitation; understandably some of these families opted to continue their follow-up at St James’s when they observed the often dramatic effect of more aggressive antibiotic and nutritional treatment.

Anita MacDonald

Dietitian

Sue Morton Physiotherapist

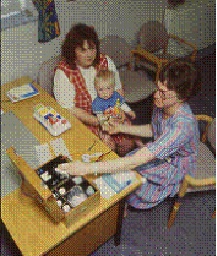

As the numbers of referrals increased the medical, nursing and allied professionals – Sue Morton (physiotherapist) and Anita MacDonald (dietitian) – gave more than their allotted time to the CF service and became increasingly knowledgeable, indeed experts, in the treatment of CF – but also they were increasingly over-worked. Indeed, it was not unusual to see Anita MacDonald on the children’s ward late into the evening.

A moment’s diversion. In 1987 Anita MacDonald, our dietitian, left Leeds to work at Birmingham Children’s Hospital where she sought more involvement in metabolic disorders. She had a brilliant career making major contributions in the treatment of many paediatric disorders particularly phenylketonuria and achieving a PhD, a Professorship and in 2016 being awarded an OBE.

Christine Silburn