Physiotherapy

Introduction

Chest physiotherapy is an integral part of the management of CF. The aims are to reduce airway obstruction by improving the clearance of secretions, to reduce the severity of the infection by clearing infected material, and to maintain optimal respiratory function and exercise tolerance (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2002). Treatment is continually monitored and modified according to the individual’s requirements.

Airway clearance techniques

The Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques (Pryor et al, 1979; Webber et al, 1986; Webber, 1990)

This consists of three breathing techniques

Breathing control is used between other techniques to allow relaxation.

Thoracic (chest) expansion exercises with the emphasis on inspiration, expiration being quiet and relaxed.

The forced expiration technique or huff is used to mobilise and clear secretions. One or two forced expirations are combined with a period of breathing control. A huff from high lung volume (when a breath has been taken in) will clear secretions from the upper airways and a huff from mid to low lung volume will clear secretions from the lower more peripheral airways.

The Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques (ACBT) are not a rigid treatment method and can be modified to suit all ages and individual needs. It may be used in conjunction with other airway clearance techniques as required.

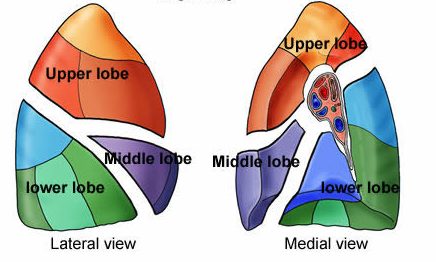

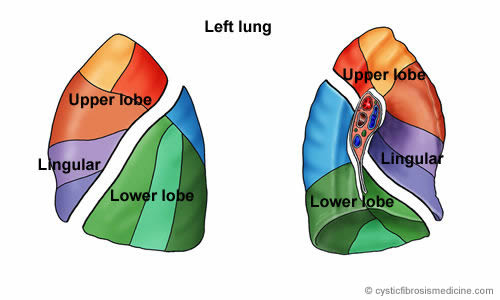

Postural drainage

The aim of postural drainage is to allow gravity to assist the drainage of respiratory secretions. There are 11 different positions which are based on the anatomy of the bronchial tree and are aimed at draining particular lobes or lung segments. The right lung is divided into three lobes (upper, middle and lower) while the left lung has only two lobes (upper and lower). Postural drainage may be used in conjunction with other techniques, e.g. ACBT, positive expiratory pressure (PEP) and percussion. It involves positioning to allow gravity to assist drainage of secretions based on the bronchial tree anatomy. Patients require an individual regimen of positions to manage their airway clearance. This may be altered with disease progression or changing symptoms. Positions can be modified if poorly tolerated or inconvenient.

Effective postural drainage equipment for home use is provided from voluntary contributions to the CF Unit funds.

Right lung anatomy

Right upper lobe

Apical segment (1)

Posterior segment (2)

Anterior segment (3)

(3

Right Middle lobe

Lateral segment (4) & Medial segment (5)

Right Lower Lobe

Superior segment (6)

Anterior basal segment (7)

lateral basal segment (8)

posterior basal segment (9), medial basal segment (10)

S

Left Upper lobe

Left upper lobe (superior division)

Apico-posterior segment (11,12)

Anterior segment (13)

Left upper lobe (lingular division)

Superior segment (14), Inferior segment (15)5)

Left lower lobe

Superior segment (16)

Posterior basal segment (17)

Antero-medial basal segment (19)

Percussion/Chest clapping

This can be performed with cupped hand(s) over the area being drained. It should be performed for approximately 15-20 seconds with pauses for five seconds or longer to minimise the risk of desaturation in patients with moderate or severe lung disease (Pryor et al, 1990). Mechanical percussors have not been shown to increase sputum clearance or lung function above that achieved with conventional manual techniques (Pryor et al, 1981).

Percussion in short bursts can be used with ACBT until independent effective treatment can be performed by the individual. Self treatment is initially supervised and this continues until the patient, carer and physiotherapist consider the treatment is carried out effectively. At the time of respiratory exacerbations, assisted treatments are usually preferable.

Positive expiratory pressure (“PEP”) devices

Positive expiratory pressure is used to open up and recruit obstructed lung, allowing air to move behind secretions and assist in mobilising them. Breathing out against a slight resistance (10 to 20 cms of water) prevents the smaller bronchial tubes from collapsing down and thus permits the continuing upward movement of any secretions (Tyrell et al, 1986; Falk & Anderson, 1991). The technique also allows the patient more independence.

Positive expiratory pressure devices are available as a mask or a mouthpiece, (figure 3), the suitability of which is discussed with the physiotherapist. When assessing patients suitable for a PEP device, one of the eight available resistances (diameters from 1.5 to 5mm) is selected to produce an expiratory pressure of between 10 and 20cm of water during the middle phase of expiration. The resistance is checked regularly with a manometer to ensure the desired pressure is maintained.

The treatment can be performed in the sitting or postural drainage position. The technique involves a number of breaths, with slightly active expiration, through the mask or mouthpiece followed by a period of huffing, coughing and breathing control. This cycle is repeated as required until maximum clearance of secretions is achieved. It may be combined with other physiotherapy techniques. Bubble PEP has developed from conventional PEP therapy and can be useful in younger children giving the benefits of positive pressure together with distraction focus and fun.

Astra PEPPari PEPFigure

Positive expiatory pressure devices

Most benefit is obtained by patients who produce sputum and have obstructed airways, where premature airway closure during expiration contributes to retained secretions. PEP permits greater patient independence and is useful when conventional techniques may be difficult. In patients with a previous pneumothorax or bullae evident on the chest X-ray or CT imaging, caution should be

exercised. PEP should not be used in patients with perforated ear drums.

Oscillatory devices

The Flutter VRP1 (Scandipharm International, Powys, UK) is a small plastic device, which contains a large ball bearing that repeatedly interrupts the outward flow of air. This generates a controlled oscillating positive pressure, which mobilises respiratory secretions. A Flutter session consists of about 10-15 breaths followed by huffing and breathing control. This is repeated for 15 or 20 minutes depending on individual need.

Studies have been conducted to assess the effect of the Flutter VRP1 with both positive (Konstan et al, 1994; Homnick et al, 1998) and negative (Pryor et al, 1994) results. The Flutter can be used as an adjunct to other forms of physiotherapy or as a treatment in its own right (McIlwaine et al, 1997). The Flutter resulted in greater improvement in pulmonary function after one week in hospitalised patients when compared to conventional chest physiotherapy, although there was no difference detectable after two weeks treatment (Gondor et al, 1999).

Figure 4: Oscillatory devices

Figure 3 Acapella device

The Acapella (DHD Healthcare, Wampsville, NY 13163, USA) is a vibratory PEP device where the resistance can be set, and is not position dependent. This means that, unlike the Flutter, it can be used easily in postural drainage positions without compromising patient comfort or efficacy of treatment.

Autogenic drainage

This term describes a series of breathing exercises devised by the Belgian physiotherapist Jean Chevaillier. The aim is to dislodge and collect mucus from the lungs and then clear these secretions by breathing at various lung volumes (Chevaillier, 1984; Schoni, 1989).

There are three phases – the Unstick, Collect and Evacuate when breathing at low, mid and high lung volumes to mobilise, collect and expectorate secretions respectively. It should be taught by a person skilled in its use and trained in the procedure. A modification of the original technique is now used in Germany (David, 1991) and a recent trial has provided evidence that the technique is of benefit (Miller et al, 1995).

We have found autogenic drainage a difficult technique to use in young children, but it may be beneficial in the young adolescent and in adults who are productive of sputum and can co-operate fully, demonstrating effective breathing control. This technique has been found to combat some associated problems of wheeze and airway collapsibility and has been well received, particularly in those individuals who suffer with uncontrolled coughing.

This is not an exhaustive list of techniques, but is representative of those most commonly used. All adjuncts to chest physiotherapy are assessed for effectiveness, suitability and affordability by the specialist team.

Physical activity

Aerobic exercise is beneficial for all patients with CF and should be encouraged. Most individuals find exercise enjoyable with supervised exercise programmes improving both cardiorespiratory fitness and morale, and leading to a higher degree of perceived competence, improved self-esteem and quality of life. Exercise should complement chest physiotherapy. The two treatment techniques combined tend to increase sputum clearance (Andreasson et al, 1987; Bilton et al, 1992; Baldwin et al, 1994; Webb et al, 1995).

Even in the very young baby an increased level of activity is promoted. Parents are advised to encourage the whole family to adopt an active lifestyle, so making exercise part of normal family life. They are shown how to stimulate and encourage age appropriate exercise from the time of diagnosis, and the resulting benefits to the child are discussed.

The medical literature is supportive of the importance of regular aerobic exercise to maintain good lung function (Selvadurai et al, 2004). Anecdotally we have observed very strong associations between those patients who regularly participate in such exercise and those who maintain good lung function and outcomes.

There are few activities that the individual with CF cannot participate in following discussion with the CF team. The following list gives examples of sports which may cause issues:

• Contact sports e.g. martial arts, rugby are discouraged if the patient has an indwelling venous access device

• Scuba-diving is not advised due to the increased risk of pneumothorax (BTS guidelines, 2003). Snorkelling is an enjoyable and acceptable alternative

• Horse-riding is an acceptable activity but grooming or ‘mucking out’ should be avoided due to the associated increased exposure to fungal spores

• Heavy weight training should be avoided if the patient has an implantable venous access device, as the catheter may become dislodged, and there is a risk of inguinal hernia with all patients

High frequency chest wall oscillation (The Vest TM)

This passive form of airways clearance is used widely in the USA and some CF Centres in this country are presently assessing it. Research has shown that The Vest TM is as effective as conventional forms of chest physiotherapy (Braggion et al, 1995), but it is a costly therapeutic option. The VestTM mobilises pulmonary secretions by rapidly inflating and deflating, thereby compressing the chest wall. This movement is thought to dislodge and thin the sputum moving it into more proximal airways and aiding expectoration. We advocate a more active and participative approach to airways clearance, although certain patients may benefit from a trial of the device with a view to longer term treatment.

Progression of airways clearance techniques

It is important that all patients are seen by an experienced physiotherapist with specialist knowledge in the treatment of CF as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. If routine care is carried out at a local hospital it is essential to have additional advice from the specialised team at a Regional CF Unit.

Following diagnosis through neonatal screening the newborn infant will be seen regularly by the physiotherapist. The parents will be taught how to identify increased respiratory symptoms and when it is appropriate to increase the frequency and nature of the treatment regimens. Passive manual techniques will be demonstrated using positioning, percussion and vibrations. The families will have the opportunity to practice these at home in order to become proficient and confident in their use when respiratory symptoms occur (Prasad & Main, 2006). The use of the head down position in postural drainage is avoided at least for the first year to prevent any possible negative effects from gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR), a common condition in infants with CF. Gastro-oesophageal reflux increases the risk of aspiration of small amounts of food/fluid into the lungs. GOR is associated with a more rapid deterioration in lung function and may be exacerbated by head-down postural drainage (Button et al, 1997; Button et al, 2004).

Treatment regimens are designed for each individual. Active participation in airway clearance is encouraged and initiated at appropriate ages. Blowing is the first active participation in treatment and is introduced as soon as the child is old enough. The forced expiratory technique (FET) and coughing are introduced between the ages of three and five years. Between five and seven years of age thoracic expansion exercises are incorporated to replace the blowing. The treatment programme is regularly re-assessed and modified to suit the individual patient.

The development from this programme towards self-treatment is encouraged and stimulated. Some children will be proficient in self-treatments from the age of 11 years, while others prefer assisted treatments for longer. It is important that adults with CF are educated in, and become responsible for, their own chest care. They must recognise the signs of increased infection and contact the hospital at these times for assessment and treatment with intravenous antibiotics if necessary. Those who have not attended a specialist CF Unit previously often require considerable education, explanation of the importance of doing their chest physiotherapy treatment at home, and encouragement to follow this programme on their own, now that they may no longer have parental supervision. These patients require regular input, support and monitoring from a physiotherapist experienced in dealing with and treating adults who have CF.

Most adults with CF produce sputum, and a daily session of appropriate chest physiotherapy is encouraged with the type and timing adapted to patient needs and lifestyle. Treatment may be increased to twice daily and more for patients producing excess sputum, and during an exacerbation of their chest symptoms. Exercise is actively encouraged for all patients, both for outpatients and whilst in hospital, adjusting the exercise programme to each individual’s requirement.

Conclusions

With modern treatment many young patients with CF have no regular cough and produce no sputum for many years. However, there is evidence that even in patients with mild chest involvement regular daily physiotherapy helps to maintain respiratory function. If the patient has a productive cough, physiotherapy should be performed at least once daily, and more frequently with increasing symptoms. We consider that regular monitoring of the patient’s and family’s technique by a physiotherapist who is expert in the various techniques used in the treatment of CF is essential (Morton et al, 1988; Worthington & Kelman, 1996). Lung damage does develop in asymptomatic individuals and it is imperative that effective physiotherapy techniques are routinely undertaken to clear secretions and protect the airways from mucus plugging.

Sputum induction

It is uncommon for young children to expectorate sputum. Older children and some adults may only produce sputum with moderate to advanced disease. Early detection, identification and treatment of lower respiratory tract infection are an essential component of the management of CF. Cohort isolation and early intensive treatment following initial isolation of P. aeruginosa, results in a reduced incidence and prevalence of chronic P. aeruginosa infection. Early infection can be eradicated.

Sputum induction with nebulised hypertonic saline is safe and well tolerated. It can be delivered in the clinic. Four mls of 6% or 7% saline is given via a standard nebuliser 10 minutes after 2.5mg of nebulised salbutamol. The patient is assessed with chest auscultation, respiratory function tests and oxygen saturation before and after the saline inhalation (Ho et al, 2004; De Boeck et al, 2000).

In our study of sputum induction in children with CF, a total of 43 tests were performed (median age five years, range 1.2 to12 years). Specimens obtained by sputum induction were significantly more likely to give additional microbiological information than standard specimens, p=0.006 (Ho et al, 2004).

We advocate obtaining an induced specimen when standard cough swab specimens do not provide useful information in the following situations; if a patient has a new cough that has not responded to empirical oral or intravenous antibiotics, has new chest x-ray changes, or converts to P. aeruginosa antibody positive.

Key points

• Chest physiotherapy is integral to the management of CF

• Even in patients with mild chest involvement, regular daily physiotherapy helps to maintain respiratory function

• A range of effective physiotherapy techniques can be used according to individual patient needs

• Induced sputum may provide useful diagnostic information

• Aerobic exercise benefits all patients and should be encouraged from diagnosis so that it becomes a part of daily life

• Physiotherapy should be performed at least once daily and more frequently with increased symptoms

References

Andreasson B, Jonson B, Kornfalt R, et al. Long term effects of physical exercise on working capacity and pulmonary function in CF. Acta Paediatr Scand 1987; 76: 70-75. [PubMed]

Baldwin DR, Hill AL, Peckham DG, et al.. Effect of addition of exercise to chest physiotherapy on sputum expectoration and lung function in adults with cystic fibrosis. Resp Med 1994: 88: 49-53. [PubMed]

Bilton D, Dodd ME, Abbot JV. et al. The benefits of exercise combined with physiotherapy in the treatment of adults with cystic fibrosis. Resp Med 1992: 86: 507-511. [PubMed]

Braggion C, Cappelletti LM, Cornacchia M, et al. Short-term effects of three chest physiotherapy regimens in patients hospitalized for pulmonary exacerbations of cystic fibrosis: a cross-over randomised study. Pediatr Pulmonol 1995; 19: 16-22. [PubMed]

British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines on respiratory aspects of fitness for diving. Thorax 2003; 58: 3-13. [PubMed] [Link]

Button BM, Heine RG, Catto-Smith AG, et al. Postural drainage and gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 1997; 76: 148-150. [PubMed]

Button BM, Heine RG, Catto-Smith AG, et al. Chest physiotherapy, gastro-oesophageal reflux and arousal in infants with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 2004; 89: 435-439. [PubMed]

Chevaillier J. Autogenic drainage. In: Cystic Fibrosis: Horizons. Lawson D (ed). Churchill Livingstone, London 1984: 65-78 David A. Autogenic drainage – the German approach. In: Pryor JA. (ed). Respiratory Care. London. Churchill Livingstone, 1991: 65-7.

Cystic Fibrosis Trust Clinical Guidelines for Physiotherapy Management of Cystic Fibrosis. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Cystic Fibrosis. London. Cystic Fibrosis Trust, January 2002. [Link]

David A. Autogenic drainage – the German approach. In: Pryor JA. (Ed). Respiratory Care. London. Churchill Livingstone, 1991: 65-78.

De Boeck K, Alifier M, Vandeputte S. Sputum induction in young cystic fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J 2000; 16: 91-94. [PubMed] .

Falk M, Anderson JB. Positive expiratory pressure (PEP) mask. In: Pryor A, editor. Respiratory Care. Edinburgh. Churchill Livingstone, 1991: 51-63.

Gondor M, Nixon PA, Mutich R, et al. Comparison of flutter device and chest physical therapy in the treatment of cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbation. Pediatr Pulmonol 1999; 28: 255-260. [PubMed]

Ho SA, Ball R, Morrison LJ, et al. Clinical value of obtaining sputum and cough swab samples following inhaled hypertonic saline in children with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Pulmonol 2004; 38: 82-87. [PubMed]

Homnick DN, Anderson K, Marks JH. Comparison of the flutter device to standard chest physiotherapy in hospitalised patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. Chest 1998; 114: 993-99. [PubMed]

Konstan MW, Stern RC, Doershuk CF. Efficacy of the Flutter device for airways mucus clearance in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 1994; 124: 689-693. [PubMed]

McIlwaine PM, Went LTK, Peacock D, et al. “Flutter versus PEP”: a long term comparative trial of positive expiratory pressure (PEP) versus oscillating positive pressure (flutter) physiotherapy techniques. Pediatr Pulmonol 1997; Suppl 14: A339.

Miller S, Hall D0, Clayton CB. Chest physiotherapy in cystic fibrosis: A comparative study of autogenic drainage and the active cycle of breathing techniques with postural drainage. Thorax 1995; 50: 165-169. [PubMed]

Morton S, Gilbert J, Littlewood JM. The current physical therapy regimens of 108 consecutive patients attending a regional cystic fibrosis unit. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988; 143: 110-3. [PubMed]

Prasad A, Main E. Routine airway clearance in asymptomatic infants and babies with cystic fibrosis in the UK: obligatory or obsolete? Phys Ther Reviews 2006; 11: 11-20. [PubMed]

Pryor JA, Webber BA, Hodson ME, et al. Evaluation of the forced expiration technique as an adjunct to postural drainage in treatment of cystic fibrosis. BMJ 1979; 2: 417-418. [PubMed]

Pryor JA, Parker RA, Webber BA. A comparison of mechanical and manual percussion as adjuncts to postural drainage in the treatment of cystic fibrosis in adolescents and adults. Physiotherapy 1981; 67: 140-141. [PubMed]

Pryor JA, Webber BA, Hodson ME. Effect of chest physiotherapy on oxygen saturation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 1990; 45: 77. [PubMed]

Pryor JA, Webber BA, Hodson ME, et al. The Flutter VRP1 as an adjunct to chest physiotherapy in cystic fibrosis. Respir Med 1994; 88: 677-681. [PubMed]

Schoni MH. Autogenic drainage: a modern approach to physiotherapy in cystic fibrosis. J R Soc Med 1989; 82 (Suppl 16): 32-33 [PubMed]

Selvadurai HC, Blimkie CJ, Cooper PJ, et al. Gender differences in habitual activity in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 2004; 89: 928-933. [PubMed]

Tyrrell JC, Hiller EJ, Martin J. Face mask physiotherapy in cystic fibrosis.. Arch Dis Child 1986; 61: 598-611. [PubMed]

Webb AK, Dodd ME, Moorcroft J. Exercise and cystic fibrosis. J R Soc Med 1995; 88(Suppl 25): 30-33. [PubMed]

Webber BA, Hofmeyer JL, Moran MDL, et al. Effects of postural drainage, incorporating forced expiration technique, on pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Br J Dis Chest 1986; 80: 353-359. [PubMed]

Webber BA. The active cycle of breathing exercises. Cystic Fibrosis News 1990; Aug/Sept: 10-11.

Worthington D, Kelman BA. Current physiotherapy practice of new referrals to a regional paediatric cystic fibrosis service. Physiotherapy 1996; 82: 253-257.