Anabolic steroids and Corticosteroids

There were a number of papers on the use of anabolic steroids before more effective pancreatic enzymes became available. Although they were effective, the side effects were a problem. Apparently there are fewer androgenic side effects with the newer preparations described in the most recent publications.

Anabolic steroids

1961 Kunstadter RH, Mendelsohn RS. Norethandrolone in children with and without cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. Ill Med J 1961; 120:156-161. [PubMed]

In 1961 as the chest infection progressed and increased in severity, it was very difficult, and usually impossible, to achieve normal weight gain and growth in children with cystic fibrosis. As the available pancreatic enzyme supplements were relatively inefficient, most patients took a low fat diet to avoid very unpleasant bowel symptoms; also there was a severe catabolic wasting effect from the active and increasingly severe chest infection. However, in this report of 14 children with CF treated with anabolic steroids had “remarkable gains in weight”.

Shwachman commented that he had used one such preparation (Nilevar) on 30 patients and found the drug “very useful but not to be used routinely”. This was the first of a number of reports that anabolic steroids had a favourable effect on weight gain in children with cystic fibrosis. The drugs were to become quite widely used as nutritional problems became increasingly severe as more children survived for longer and nutrition continued as an increasingly significant problem. It was not until the early Eighties that there was marked improvement in the control of the intestinal malabsorption following the introduction of the acid resistant enzymes (Pancrease and later Creon); also around that time, for those with more severe nutritional problems, more aggressive nutritional interventions such as nasogastric and gastrostomy feeds, became available. So the use of anabolic steroids gradually declined (also Dooley RR et al. J Pediatr 1969; 74:95-102. [PubMed] The subject was reviewed in 1981 by Richard Dooley (Anabolic steroids. In 1000 years of Cystic Fibrosis. Warren Warwick (ed). University of Minnesota, 1981).

1966 Good TA. Bessman SP. Anabolic steroids in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. Am J Dis Child 1966; 111:272-277.[PubMed]

These authors tried artificial stimulation of a severely ill child’s appetite with anabolic steroids with dramatic results and report the results of treating six such children given large doses of anabolic steroids, estrogen or progestational compounds. The child described was started on methandrostenolone 10mg daily. Appetite increase in 2 weeks becoming voracious, and within 3.5 months she had gained 8 kg and grown 3 cms. Acne and mild clitoral hypertrophy developed and the dose reduced to 5mg daily but when further reduced some worsening of the respiratory state occurred with some depression. Much improvement followed a change to injected estradiol valerate 20mg every 2 weeks which with 5 mg of methandrostenolone daily she did well for 10 months.

Richard Dooley commented that carefully controlled studies were needed. He noted that improvement in lung disease and resolution of clubbing had also been described by Denis JL and Panos TC (JAMA 1965; 194:855-858.[PubMed]) and he had also observed similar effects having used androgens for 6-48 months in 30 patients (below).

1969 Dooley RR, Moss AJ, Wright PM, Hassakis PC. Norethandrolone in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. J Pediatr 1969; 74: 95-102. [PubMed]

Twenty eight severely affected patients were treated in the 5 years up to 1968 with the anabolic steroid norethandrolone. All the patients showed immediate improvement in appetite, activity and weight gain; also their respiratory function improved. Six patients died and there were a variety of side effects side effects including virilisation (also Kunstadter et al, 1961 above).

However, there was great interest in this treatment as all else had failed to achieve weight gain in some of these patients. The subject was reviewed in 1981 by Richard Dooley (Anabolic steroids. In 1000 years of Cystic Fibrosis. Warren Warwick (ed). University of Minnesota, 1981 below).

1981 Dooley R. Anabolic steroids. In 1000 years of Cystic Fibrosis. Ed; Warwick WJ. University of Minnesota. 135-139.

An interesting presentation at this meeting where Richard Dooley reviewed the use of anabolic steroids in CF from the first report by Kunstadter (1961 above). The intention of the presentation was “to pique interest in other CF care providers to review their own experience with this type of therapy and to hopefully decide whether such therapy is ever indicated”.

Subjects were seen over 12 years ending in 1975 when norethandrolone was withdrawn from the American market as having no advantage over other anabolics. At least 19 patients are described. The eventual suggestion was that experience in these patients, and in other published patients, indicated that anabolic steroids may be indicated in pre-adolescent patients with progressively severe disease that cannot be controlled by conventional therapy. However, Dooley cautioned such treatment was still in the “experimental phase”. It is a sign of the times that all the patients described had succumbed to the disease by 1981.

The discussion that followed suggested that some of the experienced clinicians attending had experience using these drugs

2005 Colombo C. Battezzati A. Growth failure in cystic fibrosis: a true need for anabolic agents?. J Pediatr 2005; 146:303-305. [PubMed]

2009 Varness T. Seffrood EE. Connor EL. Rock MJ. Allen DB. Oxandrolone Improves Height Velocity and BMI in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2009:826895. [PubMed] Free PMC article available

A retrospective study to evaluate the effectiveness of oxandrolone in improving the nutritional status and linear growth of pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). Both height z score (pre-Ox = -1.64 +/- 0.63, Ox = -1.30 +/- 0.49, P = .057) and weight velocity (pre-Ox = 4.2 +/- 3.7 kg/yr, Ox = 6.8 +/- 1.0 kg/yr, P = .072) showed beneficial trends that did not reach statistical significance. No adverse events were reported.

The authors concluded oxandrolone improved the HV and BMI z score in patients with CF but larger studies were needed to determine if oxandrolone is an effective, safe, and affordable option to stimulate appetite, improve weight gain, and promote linear growth in patients with CF.

Corticosteroids

1985 Auerbach HS, Williams M, Kirkpatrick JA, Colten HR. Alternate-day prednisone reduces morbidity and improves pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 1985; 2:686-688.[PubMed]

Children aged one to 12 years with CF received 1-2 mg/kg of prednisone or placebo on alternate days for four years. The prednisone group had better lung function, lower ESR and IgG levels and required only nine admissions compared with 35 in the control group. There were no steroid induced side effects noted in this initial report (but these appeared later).

Later this and another similar study (Eigen et al, J Pediatr 1995; 126:515) both reported significant side effects including impaired glucose metabolism, cataracts and impaired growth – the latter being permanent in boys aged 18 years and older whose mean height was 4 cm less in the prednisolone treated patients (Lai HC et al. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:851-859. [PubMed]).

(Also re. steroid treatment see Pantin CFA et al. Thorax 1986; 41:34-38 [PubMed] and Greally P et al. Arch Dis Child 1994; 71:35-39 [PubMed] for effects of a course of oral prednisolone in adults with CF).

This 1985 paper excited a great deal of interest at the time but later this use of steroids, even on an alternate day basis, was shown to have far too many side effects (including osteoporosis and diabetes) to be used even though alternate day prednisolone was considered to have fewer side effects than daily dosing.

1988 Littlewood JM, Johnson AW, Edwards PA, Littlewood AE. Growth retardation in asthmatic children treated with inhaled beclomethasone diproprionate. Lancet 1988;865.[PubMed]

This was the first report of an adverse effect on growth of some children with asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroids. It is mentioned here as many children with CF receive inhaled steroids often in very large doses in an effort to control their symptoms.

Previously Graff-Lonnevig V et al 1979.[PubMed]) had reported inhaled steroids had no adverse effect on growth – surprisingly even though the height SDs fell slightly (but “insignificantly”) in the children receiving inhaled steroid treatment. Also Simon Godfrey also had found no adverse effect on growth (Godfrey et al. 1978. [PubMed]). However, during the Eighties there were 346 asthmatic children who regularly attended my asthma clinic at St James’s University Hospital in Leeds at least once between April 1984 and March 1985. They were always accurately weighed and measured by the clinic nurses at every attendance and the results recorded on a growth chart. I noticed that after inhaled steroids were started some children had an increase in weight and an impressive reduction in asthma symptoms but, unexpectedly, had no improvement or even a fall off of height growth; one would have expected their height to be accelerating as their asthma improved with the treatment.

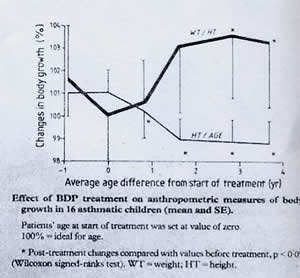

So we analysed the growth of all the children with asthma who were receiving inhaled steroids in the clinic. When the beclomethasone (BDP) group were compared with controls their SDS for height and weight were lower than controls. Of 16 patients studied before and after starting BDP treatment (figure 50) there was a significant negative inflection of growth pattern closely related to the start of BDP treatment – this demonstrated a definite adverse effect on height. We concluded that “Although it has been suggested that relevant clinical side effects from inhaled steroids are virtually non-existent, our data in children treated with inhaled steroids does not support this view”.

Height before and after starting

inhaled steroids. With permission of the Lancet

This observational study came in for heavy criticism from some respiratory paediatricians, who over some 15 years had failed to identify the adverse effect on growth (Godfrey S, et al. J Allerg Clin Immunol 1978; 62:335-339.) [PubMed] or had attributed the fall off in growth rate entirely to the delay in puberty (e.g. Balfour-Lynn L. Effect of asthma on growth and puberty. Pediatrician 1987; 14:237-41.[PubMed]).

For example L. Balfour-Lynn states – “The main cause of growth retardation in the past was the long-term prophylactic use of oral corticosteroids. Since the advent of inhalation steroids, this has no longer been a problem”.

However, some of our children were only 7 and 8 years old when they experienced an obvious slowing of height gain at a time when their asthma was under better control. Subsequently our observations on the adverse effect inhaled steroids on growth were confirmed in other studies although the controversy continued as, for many years, not all respiratory paediatricians were convinced.

On reflection it seemed that many of the previous clinical trials were of too short duration to reveal side effects such as adverse effects on growth. It was reassurung that observational studies from large clinics by experienced clinicians, who were personally involved in long term patient care, were still important to reveal long term side effects. The basic requirement to reveal these problems appeared to be many patients, accurately followed up by fewer doctors over longer periods of time. Yet another reason for patients with CF to attend CF centres for all or some of their care for I have repeatedly observed severe growth retardation in children with CF due to excessive and prolonged use of powerful inhaled corticosteroids.

2000 Lai HC, FitzSimmons SC, Allen DB, Kosorok MR, Rosenstein BJ, Campbell PW, Farrell PM. Risk of persistent growth impairment after alternate-day prednisone treatment in children with cystic fibrosis. N Eng J Med 2000; 342:851-859. [PubMed]

The growth 6 to 7 years after prolonged alternate-day treatment with prednisone had been discontinued, was recorded in 224 children aged 6 to 14 years with CF who had participated in a multicenter trial of this therapy from 1986 to 1991 (a treatment first reported in the paper of Auerbach et al, 1985 above). The Z scores for height of the treated patients declined during prednisone therapy; although catch-up occurred, the mean heights for boys 18 years of age or older were 4 cm less in the prednisone groups than in the placebo group, an equivalent of 13 percentile points. Among the girls, differences in height between those who were treated with prednisone and those who received placebo were no longer present two to three years after prednisone therapy was discontinued.

So amongst children with CF who received alternate-day treatment with prednisone, boys, but not girls, had persistent growth impairment after the treatment was discontinued. This was the final chapter in the long term alternate day prednisone treatment in CF first reported in CF by Auerbach et al in 1985 (above). At the time, there had been high hopes that the prednisone treatment would favourably modify the course of the chest infection by significantly suppressing the excessive damaging inflammation in the airways. Prednisolone was used in shorter studies by Pantin et al who showed no significant effect (Thorax 1986; 41:34-38. above [PubMed]) and Greally P et al. who showed over 12 weeks there was improved respiratory function and some reduction in inflammatory markers (Arch Dis Child 1994; 71:35-39. [PubMed]).

2001 Wojtczak HA, Kerby GS, Wagener JS, Copenhaver SC, Gotlin RW, Riches DW, Accurso FJ. Beclomethasone diproprionate reduced airway inflammation without adrenal suppression in young children with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2001; 32:293-302.[PubMed]

There are few studies evaluating the safety of inhaled steroids in young children. The authors prospectively administered beclomethasone diproprionate (BDP) 420 mcg daily for 2 months to 12 clinically stable young children with CF without affect on urine and blood cortisol levels, adrenal reserve, or increase in airway infection. Also there was a fall in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid inflammatory markers following the inhaled steroid treatment.

This was one of a number of small short term studies of inhaled corticosteroids in people with cystic fibrosis. Clinical experience shows that a few patients quite obviously do benefit significantly from inhaled steroids particularly young patients with troublesome wheezing and bronchial lability. However, a subsequent UK study of withdrawal of inhaled steroids from people with CF showed many patients were deriving no apparent benefit and their inhaled steroids could be withdrawn without ill effects (Balfour-Lynn et al. 2006 [PubMed]below). Presumably some of these patients would have derived some benefit at the time the steroids were started and there are a minority of children with CF who appear to derive great benefit from inhaled steroids. However, these patients were not included in Balfour-Lynn’s steroid withdrawal study as, understandably, their doctors (and almost certainly their parents!) were unwilling to stop their steroid treatment.

Also, although some paediatricians who published short term studies on inhaled steroids found it difficult to accept, undoubtedly in some children the rate of growth is affected by taking inhaled steroids in the doses used in this present study and this will be detected provided the children are followed up for longer and measured carefully and the values charted (by no means always the case in busy general paediatric clinics!). Obviously two months is an inadequate time to identify adverse effects on growth (see Littlewood et al, 1988 [PubMed] above for full discussion of the adverse effect of inhaled steroids on growth).

2002 Main KM, Skov M, Sillesen IB, Dige-Petersen H, Muller J, Koch C, Lanng S. Cushing’s syndrome due to pharmacological interaction in a cystic fibrosis patient. Acta Paediatr 2002; 91:1008-11. [PubMed]

Treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with itraconazole is becoming more widespread in chronic lung diseases. A considerable number of patients are concomitantly treated with topical or systemic glucocorticoids for anti-inflammatory effect. As azole compounds inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP3A isoforms, they may compromise the metabolic clearance of glucocorticoids, thereby causing serious adverse effects.

A patient with cystic fibrosis is reported who developed iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome after long-term treatment with daily doses of 800 mg itraconazole and 1,600 microg budesonide. The patient experienced symptoms of striae, moon-face, increased facial hair growth, mood swings, headaches, weight gain, irregular menstruation despite oral contraceptives and increasing insulin requirement for diabetes mellitus. Endocrine investigations revealed total suppression of spontaneous and stimulated plasma cortisol and adrenocorticotropin. Discontinuation of both drugs led to an improvement in clinical symptoms and recovery of the pituitary-adrenal axis after 3 months.

This observation suggests that the metabolic clearance of budesonide was compromised by itraconazole’s inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes, especially the CYP3A isoforms, causing an elevation in systemic budesonide concentration. This provoked a complete suppression of the endogenous adrenal function, as well as iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome. Patients on combination therapy of itraconazole and budesonide inhalation should be monitored regularly for adrenal insufficiency. This may be the first indicator of increased systemic exogenous steroid concentration, before clinical signs of Cushing’s syndrome emerge.

An important report as Aspergillus is increasingly common and the two drugs are used together not infrequently. The occurrence was later investigated further by the Copenhagen team. Suppression of the adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis was observed in 11 of 25 cystic fibrosis patients treated with both itraconazole and budesonide. The pathogenesis is most likely an itraconazole-caused increase in systemic budesonide concentration through a reduced/inhibited metabolism leading to inhibition of adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion along with a direct inhibition of steroidogenesis. In patients treated with this combination, screening for adrenal insufficiency at regular intervals is suggested.[PubMed] There was also a further case report from the UK [PubMed].

2006 Balfour-Lynn IM, Lees B, Hall P, Phillips G, Kahn M, Flather M, Elborn JS. On behalf of the WISE investigators. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:1356-1362. [PubMed]

On the grounds that the authors considered that inhaled steroids are widely used despite lack of evidence, this study was to test the safety of withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids with the hypothesis this would not be associated with an earlier onset of acute chest exacerbations. Patients during the 2-month run-in period, received fluticasone; they then took either fluticasone or placebo for 6 months. There was no difference in time to first exacerbation in the two groups. So in this study population (applicable to a surprising 40% of patients with cystic fibrosis in the UK), it appears safe to consider stopping inhaled corticosteroids.

Ian Balfour-Lynn

It would be wise to consider the individual patient’s clinical history prior to their starting inhaled steroids before considering withdrawing the treatment. Note that the summary does not mention the 24 patients whose steroids the clinicians were unwilling to stop. They had more asthma, more were atopic and they had more exacerbations and were in a worse condition. Many of these patients are considerably, even dramatically, improved when they commence inhaled steroids. Trials of N=1 are obviously useful in this clinical situation.

Dr Ian Balfour-Lynn is consultant paediatrician at the Royal Brompton Hospital, London. He is involved in many areas of both patient care and CF research. It was his uncle (L Balfour-Lynn) who was so critical of our 1988 letter to the Lancet reporting growth effects of inhaled steroids!!

2006 Thomson JM, Wesley A, Byrnes CA, Nixon GM. Pulse intravenous methylprednisolone for resistant allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2006; 41:164-170.[PubMed]

This is the first reported use of pulse intravenous methylprednisolone in the treatment of ABPA in CF. The authors present the clinical course of four children with CF and severe ABPA, in whom pulse methylprednisolone was used to manage the disease because of relapses or marked side effects on high-dose oral corticosteroids. Methylprednisolone pulses achieved disease control in 3 of the 4 children. However, troublesome side effects were experienced, in some cases necessitating discontinuation of therapy.

Pulse methylprednisolone may represent a treatment option for children with CF and ABPA, where ABPA fails to respond adequately to routine therapy.

2006 Lucidi V, Tozzi AE, Bella S, Turchetta A. A pilot trial on safety and efficacy of erythrocyte-mediated steroid treatment in CF patients. BMC Pediatrics 2006;. 6:17. [PubMed]

A novel strategy for delivering low doses of steroids for long periods through the infusion of autologous erythrocytes loaded with dexamethasone. A recent study suggested the feasibility of therapy with low doses of corticosteroids delivered through engineered erythrocytes in CF patients. This study presents a further analysis of safety and efficacy of this therapy. Nine patients in the experimental group received the treatment once a month for a period of 24 month.

Patients did not develop diabetes, cataract, or hypertension, or other typical side effects of steroid treatment during the follow up period. There was a constant improvement of FEV1 in patients undergoing the experimental treatment compared to a gradual decrease of the same parameter in the standard therapy group (P = 0.04). The average of clinic and radiological indexes did not vary. The number of infective relapses that have required antibiotic intravenous therapy was not different in the two groups, although the average of these episodes was slightly higher in the experimental therapy group.

The authors concluded intraerythrocyte corticosteroid treatment may stabilize the respiratory function in CF patients but is often considered too invasive by patients. The results obtained by their study may help planning an experimental, controlled, randomised study.

A novel method for administering anti-inflammatory treatment with dexamethasone to people with CF. However, there were no further studies on the technique up to 2013

2007 De Boeck K, De Baets F, Malfroot A, Desager K, Mouchet F, Proesmans M. Do inhaled corticosteroids impair long-term growth in prepubertal cystic fibrosis patients? Eur J Pediatr 2007:166:23-28.

The effect of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) on lung function and other clinical variables was studied in 27 prepubertal CF children with mild to moderate lung disease. In a prospective double-blind case-controlled study, fluticasone propionate 500 microg or placebo were administered twice daily during 12 months. There was no statistically significant difference in the evolution of lung function and the number of respiratory exacerbations between groups.

However, longitudinal growth in fluticasone patients was significantly slower than in placebo patients: 3.96 (0.29) cm versus 5.49 (0.38) cm [p<0.005, analysis of variance (ANOVA)] over the 12-month study duration. This resulted in a significant change in height standard deviation score (SDS) of -0.38 (0.09) in the fluticasone group versus -0.01 (0.07) in the placebo group (p<0.003, ANOVA). No catch-up growth was noted 1-2 years after discontinuation of inhaled steroids. The authors concluded the use of high-dose ICS in CF patients with mild lung disease may lead to persistent growth impairment.

– It is no surprise that this dose of fluticasone leads to impairment of growth – apparently in this study without any obvious clinical benefit. Although we described clearly impaired growth in some asthmatic children taking inhaled steroids over 20 years ago (Littlewood et al, 1988. Growth retardation in asthmatic children treated with inhaled beclomethasone diproprionate. Lancet 1988;865. [PubMed]) there has been a reluctance to accept our findings by many respiratory paediatricians. However, clinicians who carefully follow children who are taking substantial doses of inhaled steroids for prolonged periods and chart their growth accurately observe the quite obvious slowing of growth in some children. In fact we have observed virtual arrest of height growth in young children with CF treated with “heroic doses” of fluticasone to the extent that invasive dietary intervention was suggested! Of course, in such children the weight SD or centile for weight is usually much better than that for height.

2008 Ren CL, Pasta DJ, Rasouliyan L, Wagener JS, Konstan MW, Morgan WJ. Scientific Advisory Group and the Investigators and Coordinators of the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis. Relationship between inhaled corticosteroid therapy and rate of lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatrics 2008; 153:746-751. [PubMed]

To assess the relationship between inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) use and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis (CF) using the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis, an observational study of patients with CF in North America.

In this retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data, ICS therapy in patients with CF was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of FEV(1) decline (-1.52% vs. 0.44% pa) , decreased linear growth, and increased insulin/oral hypoglycemic use. This study looks at the use of inhaled steroids from another angle to that of Ian Balfour- Lynn. [PubMed].

– These results could have been predicted and support previous knowledge of inhaled steroids gained from experience and the few small studies already published. The growth effect is of course dependant on the dose used – sometimes the heroic doses used for various drugs for children with CF have serious side effects – one has seen growth totally arrested by very large doses of inhaled steroids in a small child with CF. The study leaves the paediatrician to decide in the case of individual patients if inhaled steroids are indicated. It is clear that there are some children who certainly do benefit from and should receive inhaled corticosteroid treatment.

2010 Ghdifan S, Couderc L, Michelet I, Leguillon C, Masseline B, Marguet C. Bolus methylprednisolone efficacy for uncontrolled exacerbation of cystic fibrosis in children. Pediatrics 2010; 125:e1259-64. [PubMed].

Four children with cystic fibrosis, deltaF508/deltaF508, who were admitted with severe respiratory distress and in whom no improvement was obtained by intensive antibiotic therapy and systemic corticosteroids. Chest computed-tomography scans showed hyperinflation and atelectasis. The severity of these exacerbations was explained neither by visible mucus plugging nor by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

The authors hypothesized that these clinical features were related to a severe inflammatory process in small airways. Therefore, a high-dose short course of methylprednisolone (1 g/1. 73 m(2) per day for 3 days) was given; all the patients’ conditions were dramatically improved, and the therapy was safe. To our knowledge, this is the first reported use of bolus methylprednisolone in the treatment of uncontrolled pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis.

– This is a very useful paper describing a treatment possibility when there is difficulty controlling severe respiratory distress as sometimes happens in young CF infants and older patients with severe pulmonary involvement.

2011 De Boeck K, Vermeulen F, Wanyama S, Thomas M, members of the Belgian CF Registry. Inhaled corticosteroids and lower lung function decline in young children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2011; 37:1091-1095. [PubMed]

A recent American registry analysis in cystic fibrosis (CF) children showed less lung function decline after starting inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use. The authors therefore examined the influence of ICS treatment on lung function in Belgian CF patients. Data from patients >= 6 yrs of age were eligible, provided entries on lung function, height and ICS use were available in two consecutive years. Data after oral steroid use or transplant were excluded. 852 subjects contributed data with 2,976 data pairs analysed, 44.9% concerning years of ICS use. Yearly % predicted decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was 1.07% lower during ICS use (p = 0.001). Subgroup analysis for age revealed that the lower FEV1 decline rate during ICS use was only statistically significant in children 6-12 yrs of age (2.56%; p = 0.0003). Baseline FEV(1) was lower by 5.89% (p < 0.0001) in ICS users for all age groups combined, but there was no difference in baseline lung function in the children 6-12 yrs of age. In 6-12-yr-old children with CF, baseline lung function was similar in ICS users and nonusers, but annualised FEV1 decline was 2.56% pred lower in ICS users. The Belgian data therefore support recent American findings.

Many trials of inhaled corticosteroids did not reach the standards considered adequate by Cochrane reviewers in 2009 – “evidence from these trials is insufficient to establish whether ICS are beneficial in CF, but withdrawal in those already taking them has been shown to be safe”.

The Cochrane reviewers’ observation regarding withdrawal of steroids refers to the study of Balfour-Lynn (Balfour-Lynn IM et al. Am J Respir Crit Care 2006; 173:1356-1362.[PubMed]). However it important to note that there were patients considered for that study whose paediatricians were unwilling to withdraw the steroid treatment; so, more accurately, steroids could be withdrawn in the majority of children. Also experience indicates that they do have a beneficial effect presumably by reducing the damaging inflammation in the airways as one would predict and they are widely used as was apparent from the Ian Balfour-Lynn study referred to above.

2016 Balfour-Lynn IM, Welch K. Inhaled corticosteroids for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 23;8:CD001915. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001915.pub5.

To assess the effectiveness of taking regular inhaled corticosteroids, compared to not taking them, in children and adults with cystic fibrosis. Randomised or quasi-randomised trials, published and unpublished, comparing inhaled corticosteroids to placebo or standard treatment in individuals with cystic fibrosis.The searches identified 34 citations, of which 26 (representing 13 trials) were eligible for inclusion. These 13 trials reported the use of inhaled corticosteroids in 506 people with cystic fibrosis aged between six and 55 years. Although the previous publications come in for the customary Cochrane criticism (!), there is little doubt that some children with CF do benefit from inhaled corticosteroids. Although the authors state withdrawal in those already taking them has been shown to be safe, this has not been shown to apply to all children on inhaled steroids as some parents and paediatricians were unwilling to stop the drugs and so were not included in the writer’s trial.

– In this reviewer’s opinion it would be wise to consider the individual patient’s clinical history prior to their starting inhaled steroids before considering withdrawing the treatment. Note that the summary of the article (Balfour-Lynn et al, 2006) does not mention the 24 patients whose steroids the clinicians and/or parents were unwilling to stop; they had more asthma, more were atopic and they had more exacerbations and were in a worse condition. Many of these patients are considerably, even dramatically, improved when they commence inhaled steroids. Trials of N=1 are obviously useful in this clinical situation.

2015 Albert BB, Jaksic M, Ramirez J, Bors J, Carter P, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL. An unusual cause of growth failure in cystic fibrosis: A salutary reminder of the interaction between glucocorticoids and cytochrome P450 inhibiting medication. J Cyst Fibros. 2015 Jul;14(4):e9-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.09.007. Epub 2014 Oct 5. [25286825] [Pubmed]Free full text A 12 ½ year old boy with cystic fibrosis presented with growth failure after itraconazole was added to a treatment regimen including inhaled and intranasal glucocorticoids. Investigations showed severe adrenal suppression. This case demonstrates the potential for exogenous glucocorticoids to accumulate when their degradation is inhibited by a CYP3A4 inhibitor – the major cytochrome P450 enzyme responsible for metabolism of synthetic glucocorticoids.. Other medications inhibiting CYP3A4 include macrolides (e.g. clarithromycin) and antivirals (e.g. ritonavir). Importantly, itraconazole is often used in combination with glucocorticoid treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Dr. Benjamin B Albert is a paediatrician at the University of Auckland School of Medicine

Corinne A Muirhead , Natalie Lanocha, Sheila Markwardt, Kelvin D MacDonald. Evaluation of Rescue Oral Glucocorticoid Therapy during Inpatient Cystic Fibrosis Exacerbations. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020 Dec 7.doi: 10.1002/ppul.25204. Online ahead of print.[Pubmed]

Kelvin MacDonald

An acute pulmonary exacerbation (APE) in Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is characterized by increased pulmonary symptoms attributed to bacterial colonization, neutrophil recruitment and inflammation. Antimicrobials, airway clearance and nutrition are the mainstay of therapy. However, when patients fail to improve, corticosteroids have been added to therapy. We retrospectively examined the use of rescue steroids in a children’s hospital from 2013 – 2017 during CF APE treatment following at least one week of inpatient therapy without expected clinical improvement.

106 encounters, of 53 unique patients: aged 6-20 years; who had FEV1 percent predicted (FEV1pp) data at baseline, admission, midpoint, and discharge; and had admission duration of at least 12 days were studied. Encounters treated with steroids had less improvement at midpoint percent change from admission in FEV1pp (4.9, ±11.3) than non-steroid group change in FEV1pp (20.1, ±24.6; p-value<0.001). Failure to improve as expected was the rationale for steroid use. At discharge, there was no difference in mean FEV1pp (p=0.76). Delays in steroid therapy by waiting until the end of the second week increased the total length of stay. Propensity matching comparing outcomes in patients without midpoint improvement in FEV1pp was also evaluated. There was no difference in admission or discharge FEV1pp between groups. Equally, no difference in FEV1pp at follow-up visit or in time until next APE was detected. Secondary analysis for associations including gender, genotype, fungal colonization, or inhaled antimicrobials were non-significant.

These data suggest rescue use of corticosteroids during APE does not predictably impact important outcome measures during CF APE treatment.

Corinne A Muirhead is in the Department of Pharmacy, Oregon Health and Science University.

Kelvin D MacDonald is paediatric pulmonologist, Oregon Health and Science University.

elsea S Davis, Anna V Faino, Frankline Onchiri, Ronald L Gibson , Lina Merjaneh, Bonnie W Ramsey, Margaret Rosenfeld, Jonathan D Cogen. SystemicCorticosteroids in the Management of Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbations. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022 Aug 31.doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202203-201OC.Online ahead of print. [Pubmed]

Chelsea S Davis

Rationale: Pulmonary exacerbation (PEx) events contribute to lung function decline in people with cystic fibrosis (CF). CF Foundation PEx guidelines note a short course of systemic corticosteroids may offer benefit without contributing to long-term adverse effects. However, insufficient evidence exists to recommend systemic corticosteroids for PEx treatment.

Objectives: To determine if systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of in-hospital pediatric PEx is associated with improved clinical outcomes compared to treatment without systemic corticosteroids.

Methods: Retrospective cohort study using the CF Foundation Patient Registry-Pediatric Health Information System linked database. People with CF were included if hospitalized for a PEx between 2006-2018 and were 6-21 years of age. Time to next PEx was assessed by Cox proportional hazards regression. Lung function outcomes were assessed by linear mixed effect modeling and generalized estimating equations. To address confounding by indication, inverse probability treatment weighing was used.

Results: 3,471 people with CF contributed 9,787 PEx for analysis. Systemic corticosteroids were used in 15% of all PEx. In our primary analysis, systemic corticosteroids were not associated with better pre- to post-PEx percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second responses (mean difference, -0.36, 95% CI: -1.14, 0.42; p=0.4) or a higher odds of returning to lung function baseline (odds ratio (OR), 0.97, 95% CI: 0.84-1.12; p=0.7), but were associated with a reduced chance of future PEx requiring intravenous antibiotics (hazard ratio (HR), 0.91 (95% CI: 0.85-0.96; p=0.002). When restricting the analysis to one PEx per person, lung function outcomes remained no different among PEx treated with or without systemic corticosteroids, but in contrast to our primary analysis, the use of systemic corticosteroids was no longer associated with a reduced chance of having a future PEx requiring intravenous antibiotics (HR 0.96 (95% CI: 0.86, 1.07; p=0.42).

Conclusions: Systemic corticosteroid treatment for in-hospital pediatric PEx was not associated with improved lung function outcomes. Prospective trials are needed to better evaluate the risks and benefits of systemic corticosteroid use for PEx treatment in children with CF.

Chelsea Susanne Davis, is at the University of Washington, Pediatrics, Seattle, Washington, United States; chelsea.davis@seattlechildrens.org.